Happy New Year to all, and best wishes that 2022 will be an improvement on the past year. (A low bar, I know.) Anyway, when I first published this post, on January 1, 2021, I wrote: I’m almost done with my research on the second half of the 1843 concert by the Milwaukie Beethoven Society. (If you missed our earlier posts on that concert, links are here and here.) But it’s New Year’s Day, and I’m not quite done writing about “Part Second.”

Well, it turns out that “not quite done” was an optimistic estimate, as I became distracted by so many other research topics and posts and never got around to discussing the second part of the Milwaukee Beethoven Society’s concert. New Year’s Day is here again, and I’m still not done, alas, but I have not forgotten and—with luck—I will finish that post some time this winter.

A spot of Spofforth to ring in the New Year…

Meanwhile, let’s start the New Year on a cheerful note by reprising last year’s festive musical selection, drawn from that second part of the Milwaukee Beethoven Society’s 1843 premiere concert:

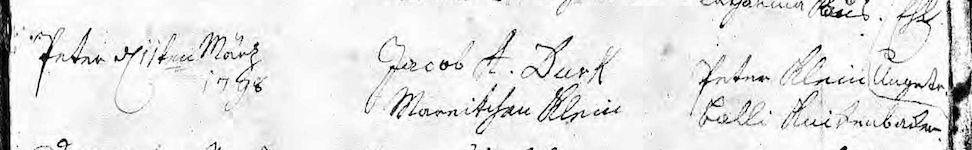

Milwaukee Weekly Sentinel March 15 1843, page 2. Click to open larger image in new window.

Continue reading