Veterans Day is today. I’m preparing a new post on one of our Clark House veterans, Mary (Turck) Clark’s youngest sibling, Benjamin Turck (1839-1926), but it’s not quite ready yet. For a wider perspective on the day—and our early Mequon veterans—here’s a post originally published at Clark House Historian on November 11, 2016, and revised, expanded and republished on November 11, 2020. I’ve also incorporated a list of Mequon’s Civil War soldiers, originally published here on May 24, 2020.

Armistice Day

One hundred and three years ago, on the eleventh day, of the eleventh month, at the eleventh hour—Paris time—the Armistice of Compiègne took effect, officially ending the fighting on the Western Front and marking the end of World War I, the optimistically named “War to End All Wars.”

In the United States, the commemoration of the war dead and the Allied victory began in 1919 as Armistice Day, by proclamation of President Woodrow Wilson. Congress created Armistice Day as a legal holiday in 1938. Starting in 1945, a World War II veteran named Raymond Weeks proposed that the commemorations of November 11 be expanded to celebrate all veterans, living and dead. In 1954 Congress and President Eisenhower made that idea official, and this is what we commemorate today. There are many veterans with a connection to the Jonathan Clark house. We honor a few of them in this post.

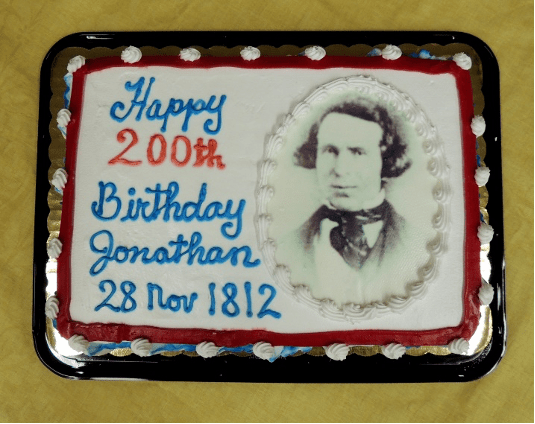

Jonathan Clark, Henry Clark, and the U.S. Army

Jonathan M. Clark (1812-1857) enlisted as a Private in Company K, Fifth Regiment of the U. S. Army, and served at Ft. Howard, Michigan (later Wisconsin) Territory, from 1833 until mustering out, as Sargent Jonathan M. Clark, in 1836. In the 1830s, Fort Howard was on the nation’s northwestern frontier. JMC’s Co. K spent much of the summers of 1835 and 1836 cutting the military road across Wisconsin, from Ft. Howard toward Ft. Winnebago, near modern Portage, Wisconsin.

Fort Howard, Wisconsin Territory, circa 1855, from Marryat, Frederick, and State Historical Society Of Wisconsin. “An English officer’s description of Wisconsin in 1837.” Madison: Democrat Printing Company, State Printers, 1898. Library of Congress. Click to open larger image in new window.

Continue reading