Today’s post is a follow-up to our recent Monday: Map Day! – Wisconsin’s Federal Roads in 1840. It features another document created by the U.S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers and preserved in the collections of the National Archives and Records Administration. Today’s drawing interests us as it documents—in some detail—the kind of road building work that Pvt. (later Sgt.) Jonathan M. Clark performed as a member of Company K, 5th Regiment, U.S. Infantry.

Webster, Jos. D, et. al., “Military Road from Fort Crawford to Fort Winnebago to Fort Howard (Wisconsin),” NARA, Record Group 77: Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Series: Civil Works Map File, File Unit: United States, accessed here, April 14, 2024.

This document interests us because after JMC left the army he, with many of his early Mequon neighbors, spent a good part of the 1840s surveying, cutting, clearing, and grubbing out some of old Washington/Ozaukee county’s earliest roads. In the process, these pioneers had to bridge streams and rivers of various sizes and depths, and find ways to keep the unpaved roadway dry and firm. How did they do it with the limited supplies and tools at hand?

Today’s document shows how the U.S. Army solved some of those issues a bit farther north, on Wisconsin’s east-west Military Road. The techniques and approaches to road construction use there may have influenced how JMC and our early county road builders solved the problems of building roads in the forests, wetlands, and open prairies of 1840s Washington county.

Beginning in the summer of 1835, Ft. Howard deployed three companies of about 100 men each to work on the Military Road during “construction season,” the dry months beginning in late-spring or mid-summer and ending when the rains and frosts of autumn arrived in September or October. In the summer and fall of 1835 and 1836, JMC worked as one of about 300 soldiers of the fifth regiment assigned to cut and construct the first westbound segment of the Military Road leading from Ft. Howard (Green Bay) toward Fond du Lac and, eventually, Ft. Winnebago. In many ways, the construction was not technically demanding; there were no tunnels to blast, mountains to climb, or canals to dig. Reports from the field describe the ground as being generally level, sometimes open prairie, sometimes forested, but often wet, boggy or swampy. There were also many small streams to cross.

The men of the Fifth Regiment did not have much in the way of building materials. Much of their work depended on picks, shovels, sharp axes, strong backs, and perhaps an ox or two to help drag the big logs and stumps out of the way. And they needed to know how to use those tools to build the driest, most stable roads and stream crossings with maximum efficiency and the smallest amount of manufactured goods. Today’s drawing illustrates how they used what they had to get the job done..

Bridges

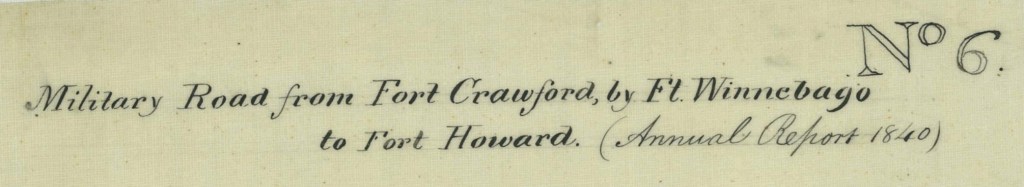

In the 1840s, the army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers employed a number of innovative bridge designs as part of Wisconsin Territory’s federal roads; the Corps was especially noted for its early use of several cutting-edge truss bridge designs. I’ll share some of those designs with you in our next post. But for the Military Road from Ft. Howard toward the portage at Ft. Winnebago, a simpler bridge was often all that was needed, as shown in this side elevation labeled “General plan of Bridges”:

Just some easily-constructed bridge abutments, made of shaped, fitted and stacked logs. Those anchor a few long logs or planks as beams, set perpendicularly to span the creek or river, topped by a road surface of thick wooden planks, laid across the beams, the whole held together with some iron nails and spikes. It’s a simple and time-tested solution for bridges of modest length and load capacity. If you’ve ever hiked a national or state park trail, you’ve probably walked across dozens of such bridges.

Roadways and embankments

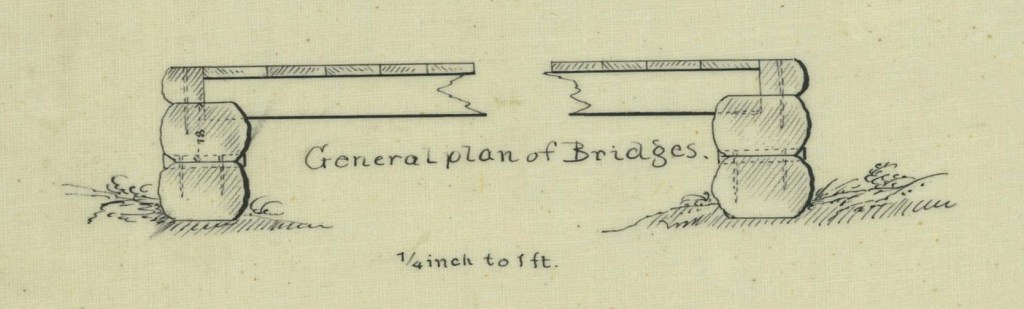

What about the roadway itself, and the embankments where the road met those small bridges? The men of the fifth regiment did not have earth moving machines, no dump trucks of coarse and fine gravel to provide a stable road base, and no asphalt or concrete for a durable road surface. The best the troops could do was to shape the road in a way that would encourage proper drainage after snowmelt and rainfall, and minimize the need for frequent re-grading the surface. Our document illustrates how they did this, in this section of a roadbed as it abuts one of the small bridges:

If I’m reading this section correctly, the roadway was 15 feet wide and raised 3 feet above the sides of the road’s drainage ditches. The sides of the roadway sloped downwards 3 vertical feet, then there was level ground extending three feet to each side of the road; this flat ground then sloped down into a two feet deep, two feet wide, drainage ditch that ran parallel with each side of the roadway.

What about the soggy areas?

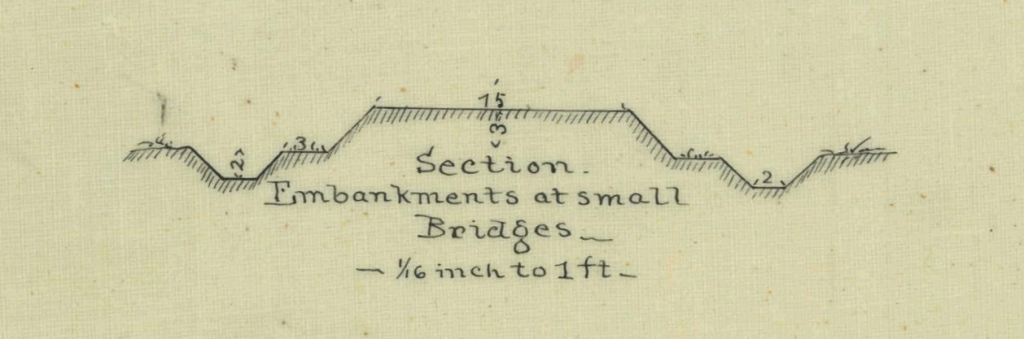

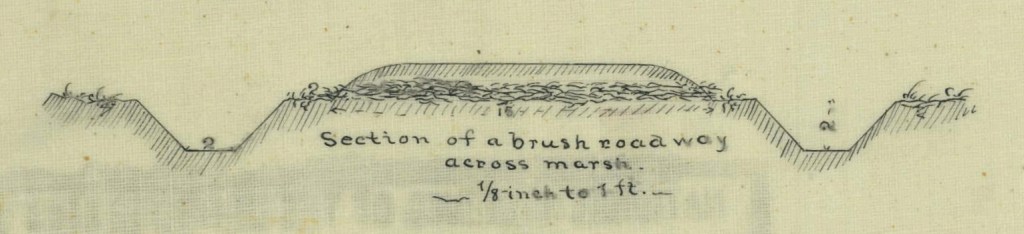

The Military Road traversed a variety of terrains, including many swamps, bogs, marshes and other permanent or seasonal wetlands. Constructing and maintaining a road in wetlands is very difficult, even with modern materials. How did JMC and his comrades solve this problem? This detail provides some answers:

The road appears to still be 15 feet wide, but the sloping elevations for drainage have been lowered and simplified.Apparently, trying to build up or elevate the road bed while crossing soggy lands was not practical or successful. The solution, above, shows that the road is still elevated a bit from the surrounding terrain, and is still framed by the parallel drainage ditches.

But if you look closely at the section, you’ll see that the smooth (earthen?) road surface has been laid upon a bed of what appears to be branches and other forest materials. Presumably these materials provided at least a bit of drainage and coherence to the base of the roadway. Or perhaps not.2 But it was probably the most practical solution to the problem using the materials at hand.

Military and Civilian Roads…

We know that Jonathan M. Clark spent the better part of summer and fall, 1835 and 1836, building the Military Road westward from Ft. Howard (Green Bay). He possibly built some of the newfangled truss bridges during his army service. We also know that JMC was very active in early Mequon-area road building projects and supervisory duties. So one wonders: how much of the “military way” of road building carried over into the early Washington/Ozaukee road and bridge projects?

For me, the current answer is “I’m not sure.” On the one hand, JMC—and many of his civilian farmer friends and neighbors—knew at least the basics of surveying, how to view roads and fences, and how to use all the available tools of the day. But I don’t think they could build roads and bridges that were up to army standards.

Why? On the one hand, the army road builders had the advice and supervision of some of the army’s elite engineers and topographers. The army crews also had, I believe, adequate supplies of hardware, such as nails and iron spikes, that may have been expensive, or scarce, in the rough rural settlements of 1840s Washington/Ozaukee county.

But most importantly, the Fifth Regiment provided three full companies of fit, trained, disciplined young men to do the work. That’s some 300 soldiers, working full-time from mid-summer to mid-autumn, only on the Military Road. In contrast, early Washington/Ozaukee county projects relied on a “labor tax” to provide workers for road projects. Each (adult, male) resident of the county was expected to perform a certain number of days or hours of labor on community projects per year, or pay a monetary tax. So there were certainly civilian workers and supervisors in early Washington/Ozaukee days, and they accomplished much. But chances are, our local men built simpler roads and simpler bridges in the early days of Mequon-area settlement than the army crews did near Fort Howard. What did those roads and bridges look like? Stay tuned for another blog post with some interesting drawings, photographs, and speculation.

What happened to the Military Road?

The path of the Military Road from Fort Howard to Fort Winnebago to Fort Crawford was important in the 1830s and ’40s, and remains so today. In fact, much of the Military Road saw continuous use and improvement over the years and is now paved over with asphalt or concrete and renumbered as various county and state highways. For a good overview, see the Wikipedia article Military Ridge Road, which includes this information:

Its modern descendant follows the route from Green Bay to Fond du Lac along Wisconsin Highway 55 and U.S. Highway 151, then west on Wisconsin State Highways 68 and 33 to Portage, where it travels west via U.S. Highway 18. The name survives as one for local streets paralleling the current highways. Military Ridge State Trail runs over a portion of its alignment. An actual 123-foot (37 m) segment of the road in its original state is also preserved in Fond du Lac County, It is located on farmland purchased by Albert and Martha Raube in 1911; Raube Road was listed in National Register of Historic Places in 1992. Other present-day reminders of the road’s legacy include Military Avenue in Green Bay and Military Road in Fond du Lac. Wisconsin Highway 55 east of Lake Winnebago is also called Military Road in some of the communities it passes through.

Postscript: Lt. Jos. D. Webster, the creator of our drawing

Our document was drawn in August, 1840—early in his military career—by Lt. Joseph Dana Webster, then initialed and dated “Sept. 1840” by Capt. T. J. Cram, and then forwarded to J. J. Abert, the Colonel of the Topographical Engineers.

Joseph Dana Webster (August 25, 1811 – April 12, 1876) “[…] was a United States civil engineer and soldier most noted for administrative services during the Civil War, where he served as chief of staff to both Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. […] He joined the U.S. army in 1838, serving as 2nd lieutenant in the U.S. Topographical Engineers. He fought in the Mexican–American War and by 1853 was captain of the U.S. Engineers.”3 He retired in 1866 as a Brevet Major General.

For more information on this interesting man, and a photograph, see Wikipedia, “Joseph Dana Webster.”

I’ll be back with more Clark House history later this week.

________________________________

NOTES:

- Road building was one of the most important tasks taken on by federal and local governments in the early years of white settlement in Wisconsin Territory, and old Washington/Ozaukee county was no exception. I’ve written and published many posts on the topic here at Clark House Historian. If you are interested knowing more, let me recommend the following:

• last week’s Monday: Map Day! – Wisconsin’s Federal Roads in 1840

• County Government – Early Records

• Monday: Map Day! – The First County Roads, 1841

• Marking out the roads

• Roads into the Woods, 1841

• Another Road into the Woods, 1841

• The county’s earliest federal roads (plural)

• a short item on JMC and a local plank road, circa 1851, in: Working at Home

• and on a general, road-related note: How’d they get here? Walking & riding - UPDATED 21 April 2024 — My original post included this footnote no. 2:

Regarding the performance of this Military Road, historian Alice Smith observed that it was “little more than a lane through the timber and a pathway over the prairie, with streams bridged and swamps ditched, the road was crude and often impassable; but it nevertheless filled the important objective of traversing Wisconsin from east to west.”

I found that quote in the Wikipedia article on the Military Ridge Road, which linked the quote to Alice Smith’s 1973 book The History of Wisconsin: Volume I: From Exploration to Statehood. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 121.

However, I just checked that quote against my copy of Smith’s vol. 1, page 121, and that quote does not appear there. So either Smith said it and the Wikipedia citation is to the wrong page, or someone else said it and needs to get proper credit. In either case, the quote agrees with and admirably summarizes much that I’ve learned about the early Military Road, so I’ll leave it here, for now. - Quote from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Dana_Webster

Pingback: The Green Bay-to-Chicago and other federal roads, c. 1840 | Clark House Historian

Pingback: Lost in the underbrush… | Clark House Historian