Continuing our look at the life of Alfred Bonniwell, today’s post focuses on two documents, the Wisconsin territorial censuses of 1846 and 1847. We’ll take a close look at the Bonniwell families as enumerated on the Wisconsin territorial census of 1846, and discuss briefly the status of the 1847 census schedules for old Washington/Ozaukee county.1

The Wisconsin Territorial census of 1846:

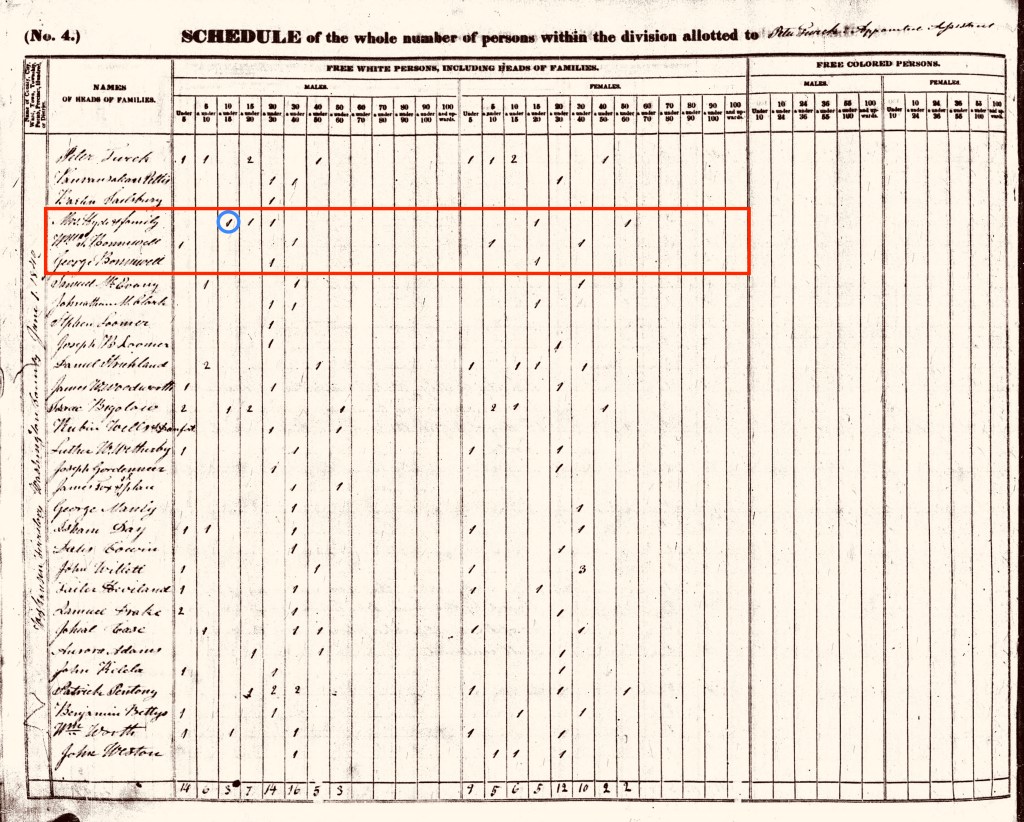

The next Wisconsin territorial census after 1842 was officially enumerated on June 1, 1846. The record of Mequon’s various Bonniwell families begins on the third line of page 43 of the Washington county schedules:

For full citation, see note 2, below; image lightly tinted. Click to open larger image in new window.

For our purposes today, the key “heads of families” and their households begin on line 3. They are the households of:

• W. T. Bonniwell . . . . . 2 males, 4 females

• Eleanor Hyde. . . . . . . .3 males, 2 females

• C Bonniwell. . . . . . . . . 3 males, 5 females

• P. Moss. . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 male, 1 female

• J. Bonniwell. . . . . . . . . 5 males, 4 females

• G. Bonniwell. . . . . . . . 2 males, 3 females

• H. Bonniwell. . . . . . . . 1 male, 3 females

We see that by mid-1846 there were seven Bonniwell family households in Mequon’s “Bonniwell Settlement.” Five were headed by Bonniwell sons: William T., Charles, James, George and Henry, and another by Bonniwell brother-in-law Philip Moss. And Matriarch Eleanor (Hills Bonniwell) Hyde still led her own substantial household.

Who’s who in 1846?

As we noted in our discussion of the 1842 territorial census, identifying “who’s who?” in each family takes some guesswork, and the identifications are never 100% certain. But let’s try and make some educated guesses about who is living with whom in each of the 1846 Bonniwell family households. Let’s start with the families of the Bonniwell sons:

Continue reading