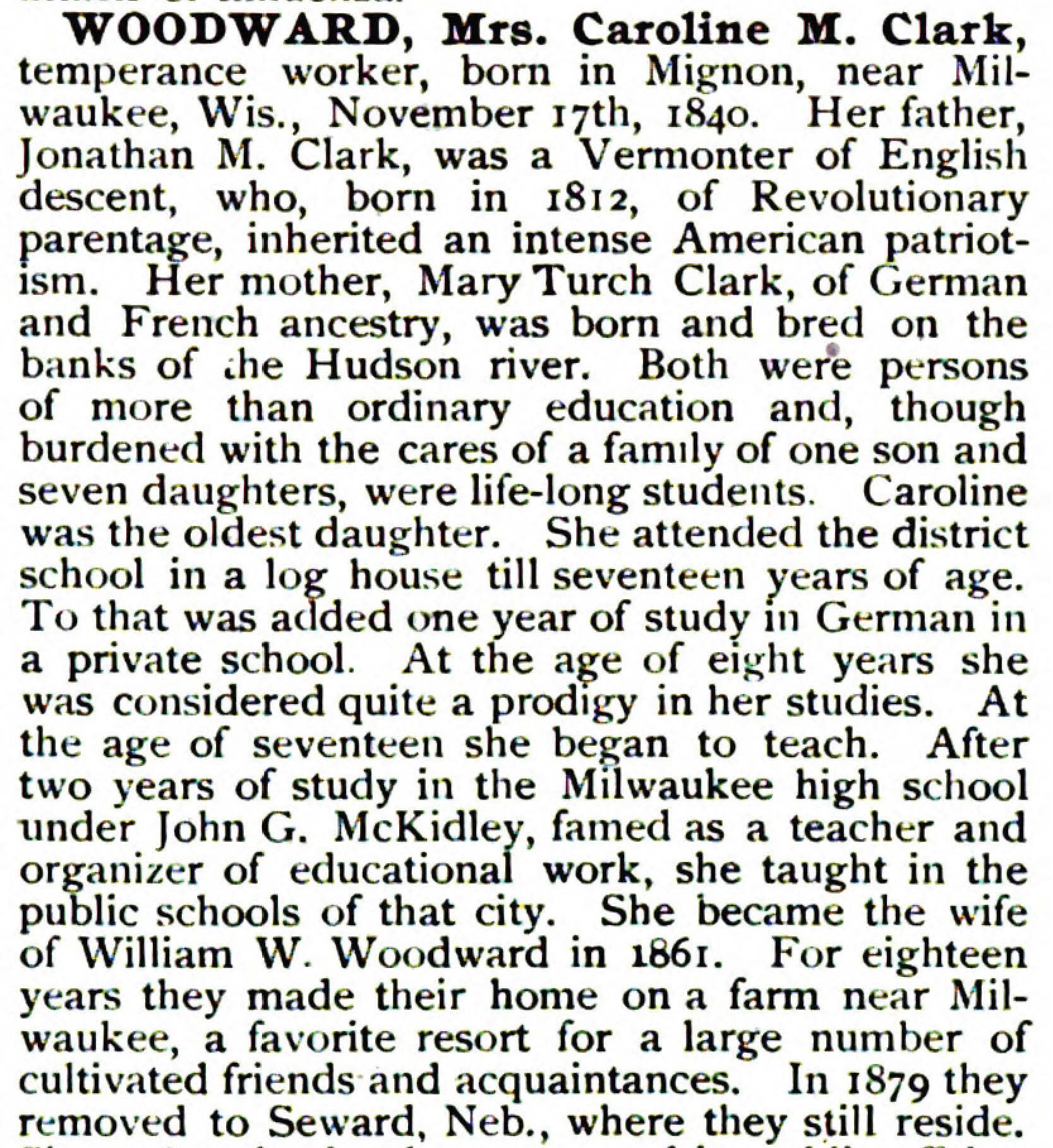

Today’s post continues our series about the life of Alfred Bonniwell, youngest son of Mequon’s Bonniwell family, and brother-in-law of Jonathan and Mary (Turck) Clark. If you missed them, our first installments are here, here and here.

UPDATED, February 2, 2022, to include additional information and a link to an earlier post about Bonniwell brother-in-law Philip Moss.

UPDATED, May 22, 2022, to correct Charles Bonniwell’s birth year (should be 1806)

Following their father’s death and burial in Montréal, Lower Canada, on October 18, 1832, the Bonniwell family was at a crossroads. Their original plan to patent land in Lower Canada had to be abandoned. As eldest son Charles Bonniwell recalled;

[…] the family received letters from the brothers who had located in New York [George and William] to come there without delay, and so [we] lost no time in taking the trip by way of Lake Champlain and Whitehall. I went to work in New York [City] where my brothers had employment at the navy yard.1

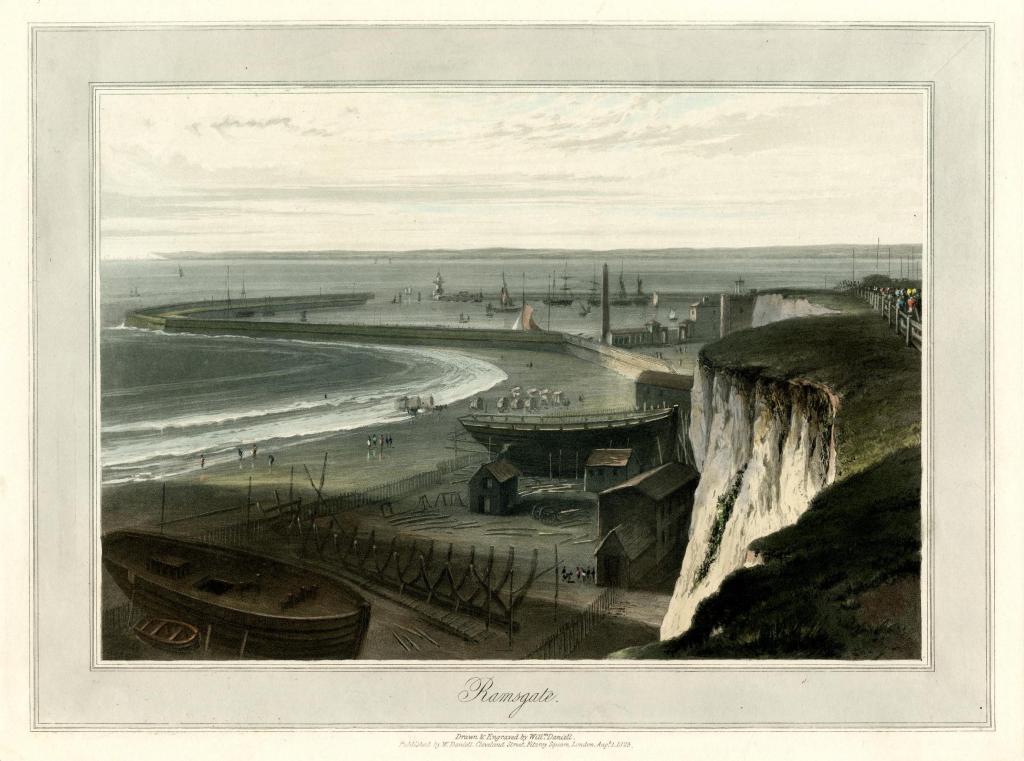

Whitehall, New York state’s port of entry at the south end of Lake Champlain, was an important waypoint for the Bonniwells, as it would also be for Jonathan M. Clark and other future Mequon neighbors. For more on that, including a handsome lithograph of Whitehall as it appeared c. 1828-1829, see How’d they get here? – JMC, the Bonniwells, and Whitehall, NY

As it turns out, Charles Bonniwell’s statement, “[we] lost no time in taking the trip by way of Lake Champlain and Whitehall,” may be a bit of a generalization. While I have not had a chance to collect or examine copies of the actual naturalization documents for all the Bonniwell boys, the modern index cards for those papers indicate that at the time of father William T. B. Bonniwell’s death the family was already dispersed at several locations. They would eventually reunite and migrate to Wisconsin Territory in 1839.

Where’s Alfred?

Many aspects of the lives of the Bonniwell family in New York are not well documented, including the activities of young Alfred T. Bonniwell. Alfred was only six and a half years old when his father died in Montréal in October, 1832. According to his naturalization papers (filed in Milwaukee on April 6, 1849, and summarized on this modern index card), we know Alfred entered the United States at Whitehall, New York, sometime in November, 1832.

This index card—and Alfred’s 1849 final citizenship document that it summarizes—are the only two official records that I have located that document Alfred’s years in New York state. Without some of the Bonniwell family papers cited in The Bonniwells, and the newspaper articles featuring Charles’s recollections, much of Alfred’s—and his family’s—life from 1832 to 1839 would be a complete mystery.

Based on brother Charles’s recollections, and other documents we have, we can assume that when Alfred came to the U.S. he was accompanied by his mother and several of his siblings, including brothers Charles (27), James (21), and Walter (age 8), and sister Eleanor (18). But not brother Henry (age about 14); more on Henry’s wanderings, below. But my understanding of which Bonniwell migrated via which port, to which destination, and what they did after arrival, is not completely clear. In fact, the family did not all travel together from Montréal to New York, via Whitehall, in November, 1832. Let’s look at the documents for more information…

Continue reading