Clark House Historian is about to begin its tenth year of investigating, interpreting and sharing the stories of the Clarks, their relatives, neighbors, friends, and the world in which they lived. With that in mind, I’ve been looking through the blog, and thinking about making a few, useful updates to the site. Chief among these would be a decent, searchable index to all those posts.

(Still) “under construction“…

From our first post in late-March, 2016, through early March, 2026, I’ve researched, written and published almost 500 Clark House Historian posts comprising about a half-million words, and illustrated with hundreds of historic maps, photographs, lithographs and other images. That’s a lot of information to organize and search.

So even though the blog has a decent SEARCH BY KEYWORDS(s) function, and each post is kind-of, sort-of indexed with SEARCH BY CATEGORY labels and SEARCH BY TAGS (mostly tagged by date or decade), it has become more difficult to find specific information and archived CHH source materials than I’d prefer. So in 2021 I started indexing the blog. Unfortunately, in the five (!) years since 2021 there’s been a long pause in indexing because, frankly, I don’t much care for indexing.

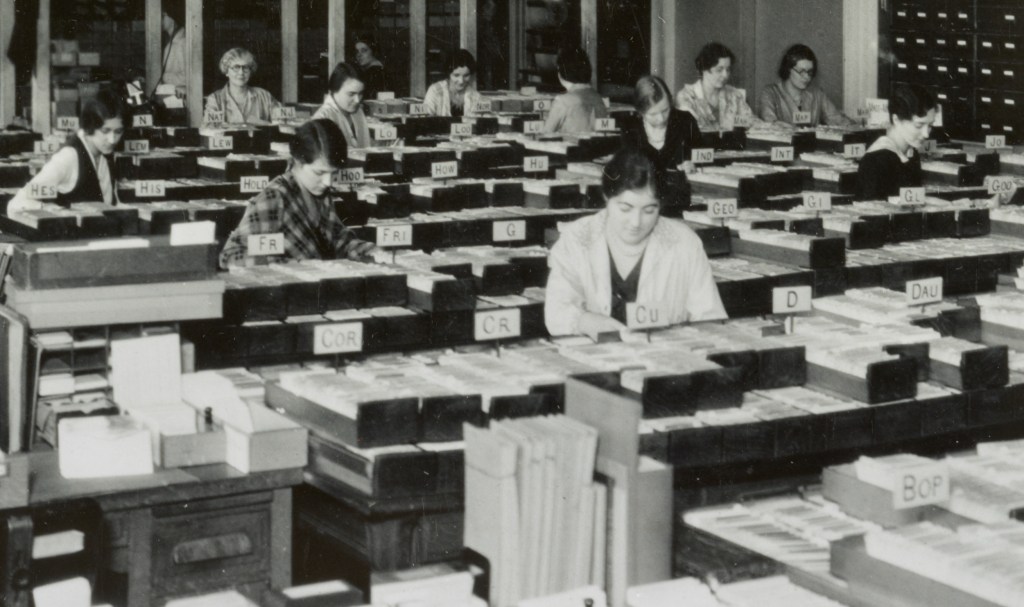

What I really need is an intelligent team of trained, experienced and eagle-eyed indexers, like these women at the catalog cards processing department of the Library of Congress in the late 1910s.

Harris & Ewing, photographer. Librarians working with catalog cards in the Processing Department of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [detail]. [Between 1917 and 1920?]. Library of Congress.

Unfortunately, I can’t afford an intelligent team of trained, experienced, and detail-oriented indexers like those women at the Library of Congress in the late 1910s. So—alas!—it’s up to me to get the indexing project moving again, bit by bit. (But, as my astute, dear father used to say, “that’s a fine speech, son…” so we’ll see.)

Anyway, if you’ve looked through the blog’s INDEX, tried the SEARCH BY KEYWORD function, and you’ve sorted by CATEGORIES, and still can’t find the CHH post, image, or other information that you’re looking for, please let me know via the blog’s CONTACT form and I’ll do my best to help.

And if you’d like to look at the most recent additions to the CHH INDEX, click “Read More” or “Continue reading” for the details…

Continue reading