Sometimes a blog is like a labyrinth…

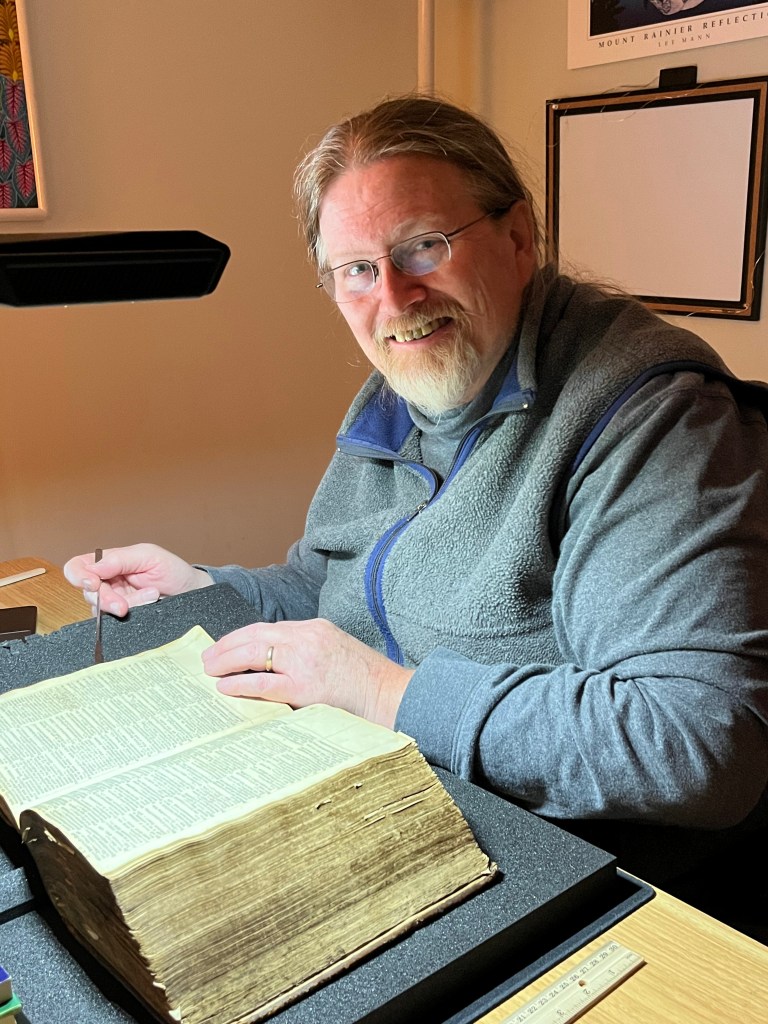

JCH Bonniwell family Bible, MS inscription “John” and drawing of a Labyrinth, First […] Concordance, sig. A1 verso (detail)

I’m looking forward to blogging more regularly, and I hope you enjoy the upcoming posts. But I’ve been publishing Clark House Historian for almost ten years (!), and I know it can be hard to navigate the blog and find the particular historical information, photos, maps and other images that you might be looking for. Today’s post has a few tips to help you make your way through the twists and turns of the Clark House Historian information labyrinth.

Tip No. 1: Click the links!

If you’d like to view a larger, clearer version of almost any image on the blog: click the image (or, sometimes, the link in the caption), and a new full-size image will open in a new window. Other links (highlighted in the blog’s signature minty-green color) will connect you with related blog posts and online sources for further information.

And by the way, you can read the blog on your phone and open and zoom in on the photos, drawings, maps and other images. But I create the CHH posts on a device with a good-sized screen, and I recommend viewing on the largest screen that you can.

Finally, and most importantly, be sure to click the Continue reading—> link, typically found after the first image and paragraph or two. There is a lot more to be found “below the fold.”

Continue reading