“Duty Calls,” Randall Munroe, XKCD, 2008-2-20 (CC-2.5 license)

Duty Calls!

Those of you that have been reading this blog for a while know that I really enjoy researching and writing about Clark House genealogy and history. I get excited chasing down obscure sources, finding unknown facts and images and then using them to craft a more detailed picture of Jonathan and Mary (Turck) Clark, their lives, family, neighbors, and to develop a clearer understanding of the era they lived in.

Regular readers also know that I’ve learned a few things along the way, one of which is that, in the words of—supposedly—Lawrence of Arabia, “All sources lie.” Which means, explains genealogist and bibliographer Elizabeth Shown Mills, “Sources err. Sources quibble. Sources exaggerate. Sources mis-remember. Sources are biased. Sources have egos and ideologies. Sources jostle for a toehold in the marketplace of ideas.

Here at CHH, I’ve blogged about and evaluated a number of local history sources over the years, most recently at JCH sources: a look at local history, part 1 and part 2. Now I’ve been asked by Jonathan Clark House museum director Nina J. Look to examine the detailed timeline of Clark House events that she has assembled over the past decade or more. This is painstaking and detailed work, and while don’t exactly enjoy proofreading and fact-checking, it’s an important thing to do. Thus, I’m in error-hunting mode these days, as I help my Clark House friends tell the most accurate and complete version of the Clark House story that we can.

ER-RA’ TUM, n.: pl. ERRATA.

Errata are errors or mistakes in writing or printing… on paper, the internet, or wherever, and I’m currently focused on finding and correcting some of them. This has inspired me to add another selection to the blog’s list of categories in the “Search CHH by Category” menu. This new category is called Errata, and I’m going to attach it to posts like this one, that are focused on particularly important, tedious, and/or persistent errors of fact. (For more on using Categories and navigating the blog in general, see our post Finding what you want: a few tips.)

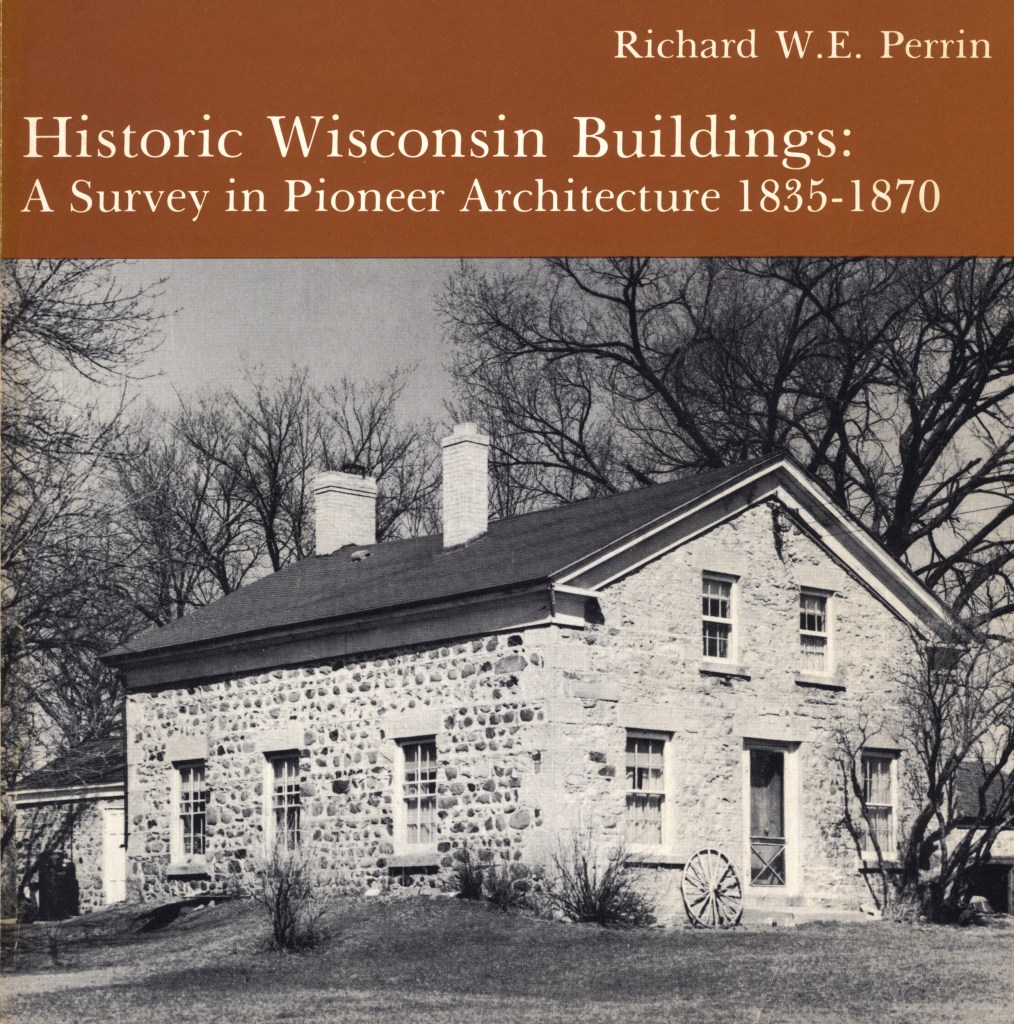

Today, our inaugural “Errata”-filled example comes from an otherwise impeccable source, architectural historian Richard W. E. Perrin and his important, lavishly illustrated book Historic Wisconsin Buildings: A Survey in Pioneer Architecture 1835-1870, second edition (Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 1981).

The book’s forward includes an overview of Richard Perrin’s long career studying early Wisconsin buildings. He participated in the first Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) of 1933 and, by 1981, had cataloged “more than 700 historic structures in Wisconsin.” In my own research, I have often referred to this book, and some of Perrin’s other writings—including some detailed articles in Wisconsin Historical Society publications—and am indebted to his scholarship.

As a bonus, the cover of the second edition features this photo of the Jonathan Clark house viewed from the southwest, The photo may date from about 1962-1981, the period of the first and second editions of Perrin’s book, but it could have been taken earlier. Perrin’s description of the Jonathan Clark house can be found on pages 91-92.

We all make mistakes…

It’s important to remember that we all make mistakes. So while Perrin’s observations as an architect and architectural historian are generally very reliable, some of the historical “facts” of the individual structures and their early owners—as related in this book—need to be carefully assessed. This is not really a critique of Perrin. I think he had to rely on incomplete and often inaccurate information from local tradition, the then-current building occupants, and less-than-scholarly local history books and other publications.

But we need to recognize that there are mistakes here, and do our best to correct them. As an example, let’s look at Perrin’s complete discussion of the Clark House on pages 91-92, from Part 3: Buildings of Stone, in the section titled Fieldstone Masonry. Perrin’s original text follows, in bold type in the grey-background quotation boxes; my commentary is interspersed in plain text.

[91] Fieldstone houses of the mid-nineteenth century often reflect Greek Revival influences in terms of floor plans and details such as doors, windows and cornices which were generally carried out in wood. But the distinctive qualities are often less those of architectural “style” then the admirable handling of the material. Sometimes fieldstone and quarried rocks were combined for very interesting effects. The old Clark house near Cedarburg is one of the finest examples of this combination.

So far so good. And it’s interesting to note that, once again, the Clark House is described as “near Cedarburg.” Which is true, and gives an indication that even as late as 1981, Cedarburg was more of a “local landmark” for Wisconsin readers than more rural and less developed post-war Mequon.

Built in 1848 by Jonathan Morrell Clark of New Jersey, the stone plate in the north gable attests both the date and the builder’s name. Would that every builder had been so thoughtful.

A minor point: Jonathan’s middle name was spelled in several ways during his lifetime, and it’s not 100% sure which was his preferred spelling. He usually signed his name “J. M. Clark.” But the preponderance of sources suggest Morrill is the preferred spelling.

More importantly, to the best of my knowledge JMC was never in New Jersey. New England? sure. New Jersey? nope.

Also the “Jonathan M. Clark | 1848” stone plate on the front of the house was—and remains—above the front door lintel of the south side of the house. And while the south, and north, sides of the house are gabled, the “stone plate” is mounted between the first and second floors of the house, and not up high, in the gable itself.

From 1870 to 1939 it was the home of the Doyle family. Catherine Doyle, a widow, was the family matriarch and one of the oldest settlers in Ozaukee County.

Widow Mary Clark and her unmarried children moved to Milwaukee circa 1861/1862. It is not known who lived and/or farmed the Clark farm circa 1861-1867. German immigrants Fred and Lena Beckmann lived and farmed on the Clark farm from 1868-1873. Catherine Doyle purchased the Clark property from Mary Clark and her daughters on April 19, 1872, not 1870. In 1873 Fred Beckmann became the proprietor of Cedarburg’s Wisconsin House hotel.

For the record, I have not done a detailed family tree or land records search for the Doyle family. They do appear on some of the earliest maps of the area, most of which date from the 1870s or later. I believe they are among the earlier immigrants to Mequon, but I don’t think that, in 1872, Catherine Doyle was “one of the oldest settlers in Ozaukee County.” A quick search of the BLM/GLO patents database shows that there were no federal patents granted in the present-day Ozaukee county to anyone named Doyle. (There are two “Doyle” patents from the 1840s in sections of Washington county, to the northwest of Mequon and Cedarburg. And on the federal census of 1870, Catherine Doyle was enumerated as 5o years old. A respectable age for the era, but other Ozaukee settlers were much older than Catherine in 1872.

Many stories were told about the Doyle “boys” who were reputed to have been either highwaymen, stagecoach robbers or train robbers. Whether fact or fiction, these stories persisted, and when the iast of the Doyles passed away, the legend was further enhanced when a large sum of money, cached between the floor joist under some loose floor boards, had been discovered.

I didn’t grow up in Mequon, but I can attest that stories of the “Doyle boys” still circulate, mainly involving the boys’ year-round (?) preference for going barefoot, and a general tendency toward living with only the bare necessities, “almost like hermits.” I can’t recall reading any news about the Dolye’s leading a life of crime, whether petty or felonious. For now, I’ll leave the study of those colorful tales—true or fabricated—to other local historians for further research.

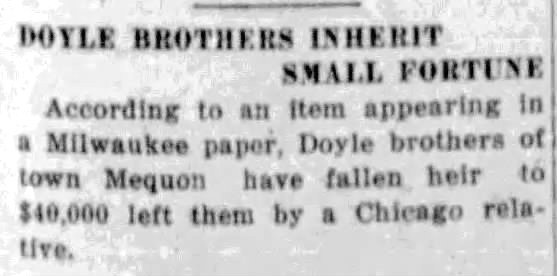

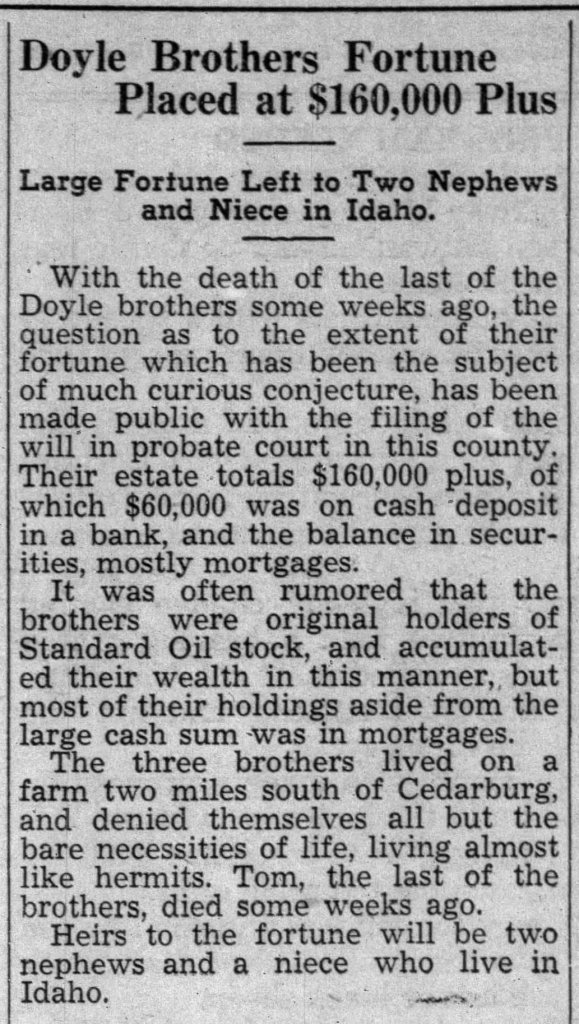

It also appears that the rumors of “cash under the floor boards” and such appear to be just rumors. I haven’t dug deeply into this, but I can share two relevant clippings (among several others) that I ran into while searching related topics. Perhaps these clippings will help re-shape the Doyles’ story in the history of Mequon?

“Doyle Brother Inherit Small Fortune,” Cedarburg News 3 Oct 1923 p 1

“Doyle Brothers Fortune,” Cedarburg News 31 May 1939 p 1

Now, where were we?

Returning to Perrin’s remarks:

For many years the house was known as the Doyle house rather than Clark house, and certainly not without cause. Standing on the corner of the Bonniwell Road and what was then the Cedarburg Plank Road, there was also a toll-gate at this point, the operation of which also give rise to reports of various irregularities somehow identified with the Doyle “boys.”

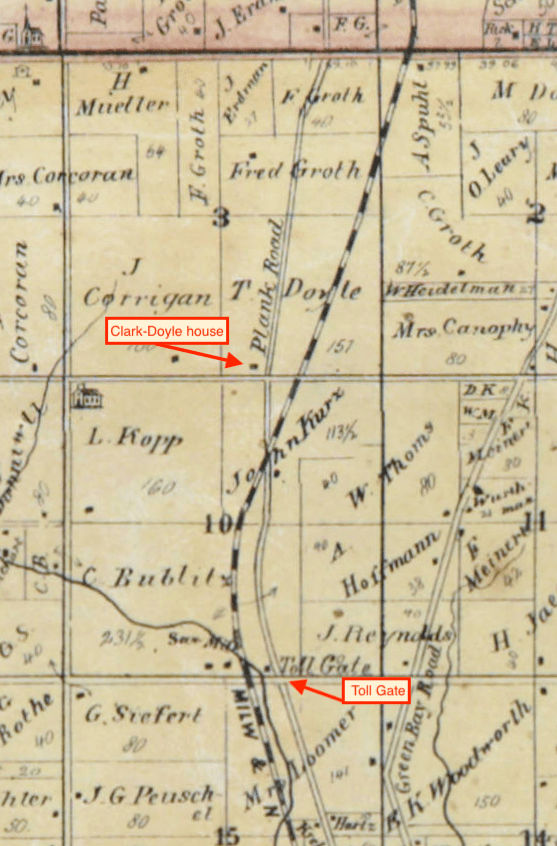

It’s not impossible that there was a toll-gate for the Cedarburg Plank Road at the Clark-Doyle house, but while this detail (below) of the 1872 Map of Washington and Ozaukee Counties, Wisconsin, 1873-74, shows the house in its correct location in section 3, on the northwest corner of modern Cedarburg and Bonniwell roads, it does not show a toll gate nearby. The only nearby toll gate for the Plank Road was located about a mile south of the Clark house, on the section 10 property of C. Bublitz, near the intersection of modern Cedarburg and Highland roads.

Subsequent to the Doyle family, the house was owned and occupied by other families, and also renovated and altered to some extent.

This is correct. For an outline of these later Clark House 0wners, see pages 5-12 of the “Jonathan Clark House Historic Structure Report,” prepared by Kubala Washatko Architects, Inc., May 2014, on file at the Jonathan Clark House Museum.

The house is built of fieldstone boulders with tooled gray limestone quoins and lintels. The south front is composed of gray limestone [92] blocks. The limestone very probably came from one of the quarries in nearby Cedarburg and after years of weathering has taken on the characteristic blue-gray tone of the material which is light cream color when freshly quarried.

On these topics Mr. Perrin is the expert and this all seems correct to me.

As for the source of the stone, an article of miscellany titled “Washington County,” published on page 2 of the Green Bay Republican, November 5, 1844, (reprinting items from the “Prairieville Freeman”) noted “Numerous ledges of lime rock are to be found in every neighborhood, and free stone of a beautiful texture up on the farm of one of the Messrs. Bonniwell in town 9 range 21.”

Freestone, is now an archaic word. According to Webster (1860), it was a noun, meaning “Any species of stone composed of sand or grit, so called because it is easily cut or wrought.” The Bonniwell farms were just a mile or two west of the Clark House on one of the first county roads (present day Bonniwell road), I would assume Jonathan M. Clark might have purchased, or been given, some of the Bonniwells’ limestone and/or freestone for the construction of the Jonathan Clark House in the 1840s.

Postscript

I realize I already have a CHH category called “Corrections & Clarifications” which, initially, was meant to include Errata as well as revisions to earlier CHH posts and revised understandings of things that were not yet known, or only partially understood, as well as out-and-out wrong “facts” and assertions found in sources. So for the moment, keep in mind that earlier CHH posts that include Errata may be currently categorized only as “Corrections & Clarifications.”

Moving forward, I’m going to reserve the “Errata” category for the kind of really irksome errors of fact, and tedious assertions of things that did not happen that keep re-appearing in the written records, but really need to go away permanently.

That’s all for now. See you soon with more “error free” (I hope!) Clark House history.