Among the real pleasures of writing a blog like this are the comments I receive from CHH readers. Recently, I heard from reader James Cornelius of nearby Grafton, Wisconsin,1 who had some thoughts about our January 24, 2025, post “Help the Historian: Mysterious (Bible?) Fragment.” 2

As the original post explained, I had been examining a number of loose Bonniwell papers, scraps, and other ephemera that were donated to the Clark House along with the Bonniwell family Bible itself, and I was particularly interested in one little fragment of printed text that had me baffled.

The mysterious fragment, sides A & B, photo credit: Reed Perkins, 2022.

In my original post, I examined the text and typography of the fragment and estimated that the it was published sometime between the late-sixteenth century (at the very earliest) and—at the very latest—the first decades of the nineteenth century. And the mentions of “Moon” and “motion” and such suggested a source that might be more scientific or philosophical, and not necessarily a sacred text, but I couldn’t think what that might be.

A new possible source: Almanacs!

In his comment, James observed: My hunch is that this triangular scrap /bookmark came from an almanac, likely as common in 1800-1820 U.K. as in U.S. a half-decade later. Many fairly good or detailed ‘scientific’ discussions appeared in the old almanacs or ‘farmer’s friends.’

I think James is on to something. Almanacs seem like a very plausible source. But how common were farmer’s almanacs in the UK, and how likely was it that the Bonniwells had access to these annual “farmer’s friends” in Chatham, Kent, England, in the years before their 1832 immigration to North America?

Almanacks in Georgian England

It turns out that the UK had a very popular annual almanac, Old Moore’s Almanac, which began publication in 1697 and is still in print.

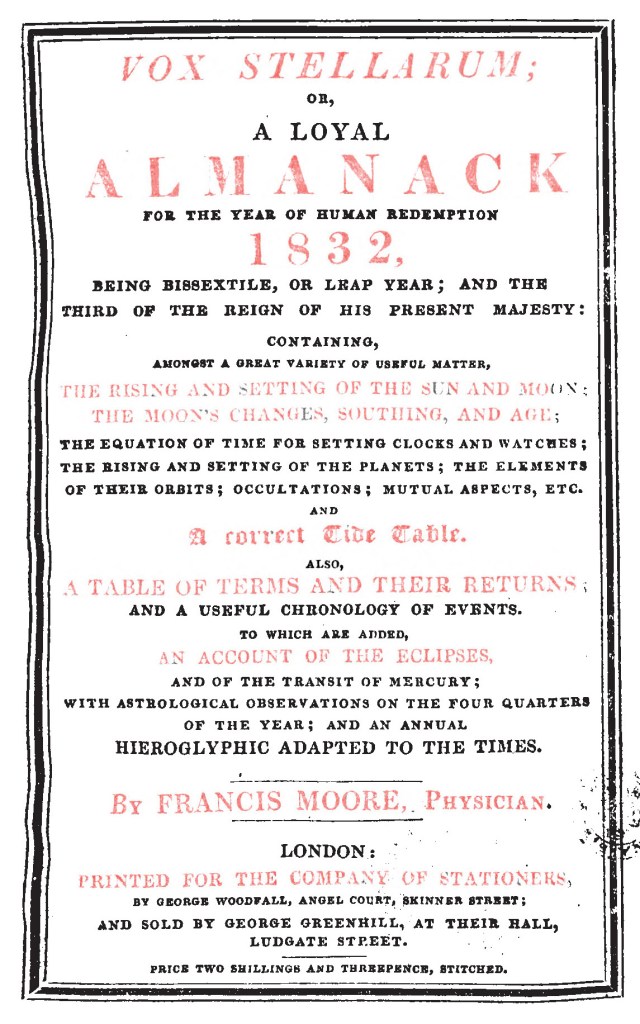

Old Moore’s Almanack. United Kingdom, n.p, 1832 (bound with same title for 1833), title page, GoogleBooks, original from Oxford University. Accessed 1 March 2025.

Old Moore’s Almanack is an astrological almanac which has been published in Britain since 1697. It was written and published by Francis Moore, a self-taught physician and astrologer who served at the court of Charles II. The first edition in 1697 contained weather forecasts. In 1700 Moore published Vox Stellarum, The Voice of the Stars, containing astrological observations; this was also known as Old Moore’s Almanack. It was a bestseller throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, selling as many as 107,000 copies in 1768.3

Needle in a haystack

Of course, finding the particular almanac that this might have come from is still very much a “needle in a haystack” proposition, which is made even more difficult by the scarcity of old almanacs in libraries, archives and online repositories. The fact is, almanacs in the U.S.—and, I assume in the UK—were almost always ephemeral items, made of inexpensive paper and considered out-of-date and disposable once the relevant day, month, or season had passed.4

And it is true, that after having served their original purpose, used almanacs were often placed in the privy to serve as toilet paper for the household. This is one of the reasons that comparatively few almanacs survive from the early 1800s, and—as far as I can tell—even fewer are available online. I was able to find a copy of Old Moore’s Almanack for the year 1832 (bound with same title for 1833), via GoogleBooks (title page image, above).

A quick browse through the 1832 and 1833 editions of Moore’s suggests that an almanac such as this is a very likely source for our mystery fragment. I cannot find our fragment in these two issues of Moore’s and, based on the lack of the long-S in these 1832 and 1833 editions, our fragment probably dates from some years before the 1830s.5

Thanks!

My thanks again to James Cornelius for the tip, and for reading Clark House Historian. If you have any thoughts, guesses, or other solutions to this little puzzle, please share them! As always, you can send a public comment to this post by using the Leave a comment space (below), or you can send me a private email via the blog’s CONTACT link. I look forward to your help!

______________________________

NOTES:

- Fun fact: Grafton is not only the place name for the Wisconsin town adjacent to the towns of Mequon and Cedarburg, it is also the name of a county in northern New Hampshire from which a number of Yankees migrated to the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada—including to Jonathan M. Clark’s purported birthplace of Stanstead, LC—in the 1790s and early-1800s. We’ll have a lot more to say about these Grafton, NH, families—including some Clark and Rix families—and their potential relationships to JMC in future posts.

- For the full story (so far!) of this mysterious text fragment, click the link to the earlier post.

- Wikipedia, “Old Moore’s Almanac,” accessed 1 March 2025.

- While copies of Moore’s are hard to find, about a dozen pre-1840 editions can be found at HathiTrust (search term: “Vox Stellarum” Almanack) or https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008696833

- UPDATE, 2 Feb. 2025: The Wikipedia article on the Long-S, particularly the section on its Decline in published works in the UK, shows that the Long-S began to fade from use by British printers in the 1790s, and had dropped out of general printing use by 1800 or so. So our fragment probably dates from the period before 1800, or thereabouts.