Recently, reader and Jonathan Clark House friend Ed Foster mentioned that he wanted to know more about how various JCH tools were used and necessary supplies were made, for example, how were lye soap or candles made? These are excellent questions, as they help us understand the day-to-day world of the Clarks and their neighbors in a more vivid and detailed way.

So, how did Jonathan and Mary Clark make candles or soap or perform many of the other home- and farm-related tasks that occupied so much of their time? Living in their pre-internet, pre-YouTube era, if they did not learn these skills from a parent or other mentor, how did they master such skills on their own? Fortunately for them, the 19th-century was a golden era of what we would call “How To” books.

The “Endless Variety” of books, circa 1837

Jonathan M. Clark mustered out of the U.S. Army at the end of his three-year’s service with Co. K, 5th Regiment Infantry, in September, 1836. While in service, he may have learned or refined a number of useful skills, especially those related to surveying and road construction. The army thought highly enough of his character and aptitude that he rose from private soldier in September, 1833, to Sergeant in 1836. He was, by several accounts, an intelligent and well-read man.

But even an intelligent, experienced man can’t know everything. For that, there were books and stores that sold them. If Jonathan, after he left the army, needed more information on the “practical arts,” he could stop by a shop such as White & Gallup’s “Variety Store” in Green Bay, and probably find the information he needed:

“Books,” advertisement from the [Green Bay] Wisconsin Democrat, 13 Jan 1838, page 1. First published 12 Dec 1837.

One of these advertised volumes caught my eye, just like it may have attracted the eye of Jonathan Clark and many other settlers in the wilds of the Wisconsin Territory in the 1830s…

MacKenzie‘s 5000 Receipts!

This is Colin MacKenzie’s popular collection of receipts—or, as we would say these days, recipes or “how to” instructions—gathered together in one useful volume titled Five Thousand Receipts in All the Useful and Domestic Arts : Constituting a Complete Practical Library and Operative Cyclopedia, published by J. J. Woodward, Philadelphia, 1829. My copy is from the library of the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History; you can get your own free PDF copy of the whole book by clicking this link to the Internet Archive.1

MacKenzie’s book is a dizzying assortment of recipes for all sorts of useful things. As he explains in the Preface:

In truth, the present volume has been compiled under the feeling, that if all other books of science in the world were destroyed, this single volume would be found to embody the results of the useful experience, observations, and discoveries of mankind during the past ages of the world.

Theoretical reasonings and historical details have, of course, been avoided, and the object of the compiler has been to economize his space, and come at once to the point. Whatever men do, or desire to do, with the materials with which nature has supplied them, and with the powers which they possess, is here plainly taught and succinctly preserved : whether it regard complicated manufactures, means of curing diseases, simple processes of various kinds, or the economy, happiness, and preservation of life.

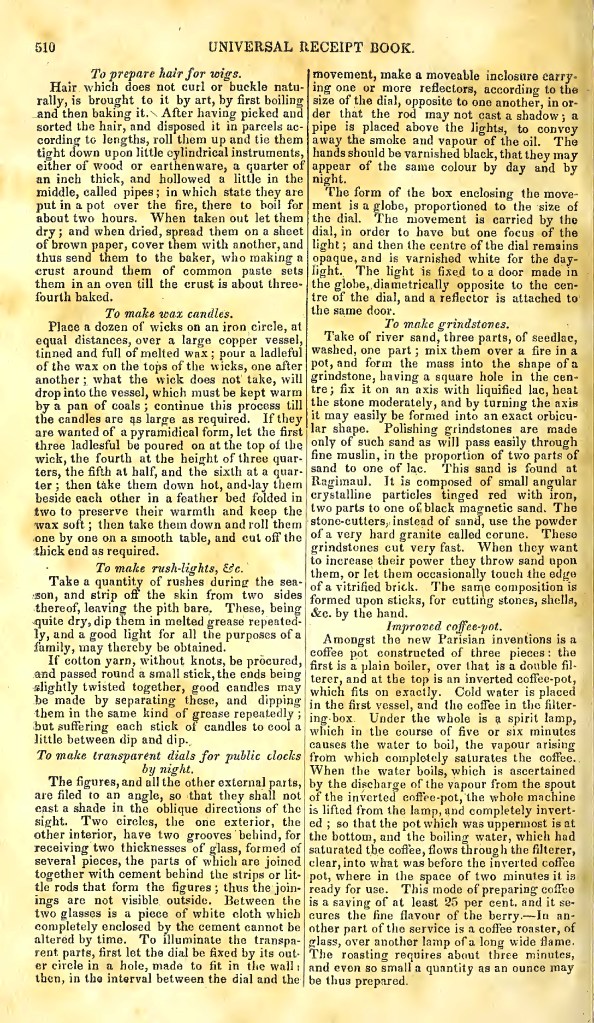

That’s one confident compiler! Did he succeed in gathering in one volume all that embodied “the results of the useful experience, observations, and discoveries of mankind during the past ages of the world”? I’ll let the reader be the judge of that. To get you started, here’s a sample page, from the closing “Miscellaneous” section of the book:

What a hodgepodge, and all on a single page!

• To prepare hair for wigs2

• To make wax candles

• To make rush-lights, etc.

• To make transparent dials for public clocks by night

• To make grindstones

• and a description of a very modern-sounding “Improved coffee-pot“

Finding your way…

The book lacks a table of contents but, fortunately, there is an index at the end, on pages 511-546. The 36-page index is organized alphabetically and appears to be pretty comprehensive. Here’s the first page of the index as an example:

Luckily for the modern reader, if you have a good searchable PDF—such as the Internet Archive copy—the PDF search function will be a big help in finding the information that interest you. And if you can’t wait to download a copy of the whole book, I have extracted the 36-page Index into a single, free, downloadable PDF file of only 4.6MB. Just click this link to open and save your own complete index to MacKenzie’s 5000 Receipts.

Postscript

Did Jonathan and Mary Clark own a copy of MacKenzie’s 5000 Receipts? We have no evidence that they did. But it was a very popular book3, and was available in the wilderness of the new Wisconsin Territory at least as early as 1837. I would not be surprised if the Clarks, or one of their relatives or neighbors, owned a copy and referred to it often.

___________________________

NOTES:

- One note regarding PDF copies of books online: you can always read the PDF online. But I find it faster, easier, and sometimes more accurate to scroll and search my own downloaded copy of a PDF book. The only drawback is that well-scanned, searchable PDFs can take up a bit of storage space, and this might be a concern on devices with limited storage. FWIW, the excellent Internet Archive scan of Mackenzie’s book takes about 85MB of storage space.

- If you read this recipe, To prepare hair for wigs, you’ll note that it ends very…oddly…to say the least. I have the suspicion that somewhere in the compiling or typesetting the tail end of To prepare hair for wigs, was lost and the ending of some other article about baked goods was tacked on. As it stands, this To prepare hair for wigs recipe is a really weird set of instructions.

Or am I missing something? Historical wig makers: I call on you for clarification! - According to MacKenzie’s Wikipedia entry, “Five Thousand Receipts (1823) was an even greater success [than his previous book]. A household economy compendium, filled with general medical information, health tips and recipes (receipts an archaic word for recipes) for all kinds of concoctions, whether culinary, medicinal or for practical household needs, Five Thousand Receipts went through at least 26 editions between 1823 and 1864 and was particularly successful in America.”

And if you’d like an original, used, print copy of the book, they are out there, and often fairly reasonably priced. For example, here’s a copy of the 1858 edition at AbeBooks for $32.00 (no endorsement implied by me or the Jonathan Clark House).

For Ed and Reed’s curiosity I refer them to the top shelf of the JCH Museum library where we have a collection of Eric Sloane books. Nina

LikeLike