Recently, we examined two competing petitions seeking a grant of land for what would become the township of Stanstead, Lower Canada. The first petition was successful, the second, not. We also suspect that many, if not most, of the signers of those petitions—including more that a dozen with Clark surnames—were probably not seriously interested in obtaining Crown lands and then pioneering in the wilderness of the 1790s Eastern Townships. As we continue our search for Jonathan M. Clark’s parents or other kin in 1790s and 1800s Lower Canada and adjacent Vermont and New Hampshire, how can we identify which Clarks might be related to JMC and which are not? What were the next steps for serious prospective Lower Canada immigrants and landowners?

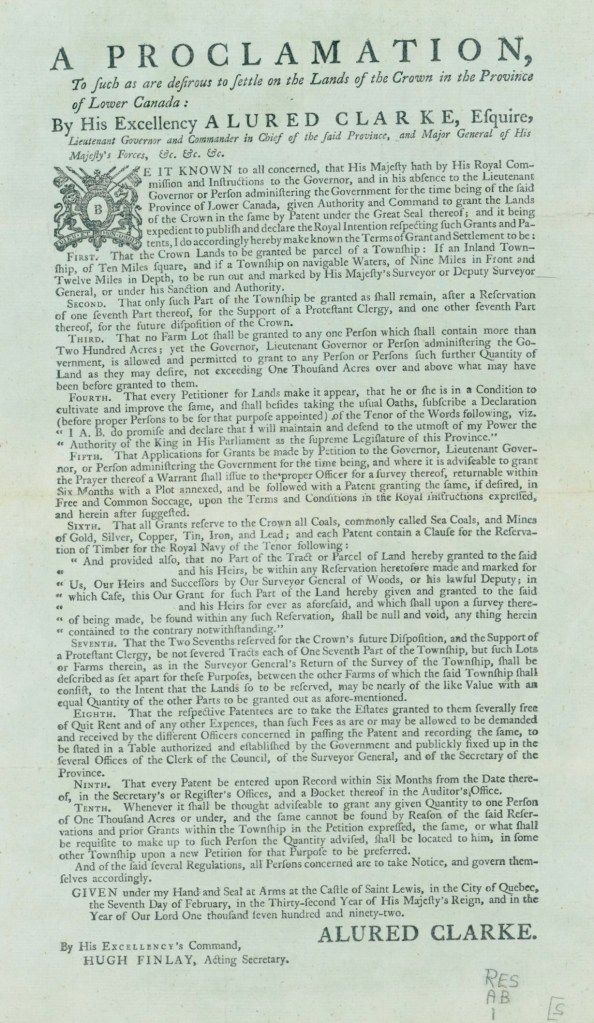

In reviewing the secondary literature (part 1 and part 2) I learned, in a general way, what the next steps were for bona fide immigrants to Lower Canada, people that actually intended to settle in the townships and that desired a land grant. But some of the details were a bit vague. So I went and found the government’s official proclamation outlining the new land grant policy:

The official proclamation, February 7, 1792

A Proclamation, to such as are desirous to settle on the lands of the Crown in the Province of Lower Canada, Lower Canada, Lt. Governor, Alured Clarke, [Quebec, Samuel Neilson, 1792]. BAnQ

The complete text of this proclamation was also published in the bilingual Quebec Gazette on Thursday, February 9, 1792. If you’re interested, BAnQ has the images of the complete February 9, 1792, issue here; the proclamation occupies all of page 1 and concludes on page 2.

Getting started

As is typical with similar announcements and proclamations, our document opens (introduction and paragraphs “First“ through “Third”) with an official description of the source and rationale of the new law and how it is to be implemented.

Paragraph “Fifth” describes the Leaders and Associates petition process that we have discussed in detail in our previous posts Searching for JMC’s roots: Stanstead’s original Associates petition, 1792 and Searching for JMC’s roots: another (!) Stanstead Associates petition, 1792. Then, as this paragraph continues, once the leader submitted a petition with the necessary number of signatures, the leader would request that the government commission a survey of the desired lands, defining the official external boundaries of the township.

Once the initial “external” survey of the new township was made and approved, the leader(s) of the new township would ask that another, “internal” survey be made. This survey would divide the township’s land into 200 acre parcels, according to the newly-marked “lot” and “range” lines. The surveyor would also identify which of these parcels were to be set aside for the one-seventh of the lots reserved for use and benefit of the Protestant clergy and the additional seventh of the lots set aside for the future use and benefit of the Crown.

Taking the Oaths

While the surveys required by paragraph Fifth were being made, it was up to all prospective land grant recipients to travel to the appointed government office and “take the Oaths,” as required by the previous paragraph:

Fourth. That every Petitioner for Lands make it appear, that he or she is in a condition to cultivate and improve the same, and shall besides taking the usual Oaths, subscribe a declaration (before proper persons to be for that purpose appointed) of the Tenor of the Words following, viz. “I A. B. [i.e., first name, surname] do promise and declare that I will maintain and defend to the utmost of my power the Authority of the King in His Parliament as the supreme Legislature of this Province.”

The exact texts of the other “usual Oaths” have been hard to find. Secondary sources indicate they were oaths of loyalty to King and country typical of that era. In addition to “taking the oaths,” land grant applicants had to prove they were “in a condition to cultivate and improve” such lands. To this end, the Land Petitions of Lower Canada, 1764-1841 files include many sworn affidavits attesting to the upright character and general suitability of the individual land grant applicants.

Coming up

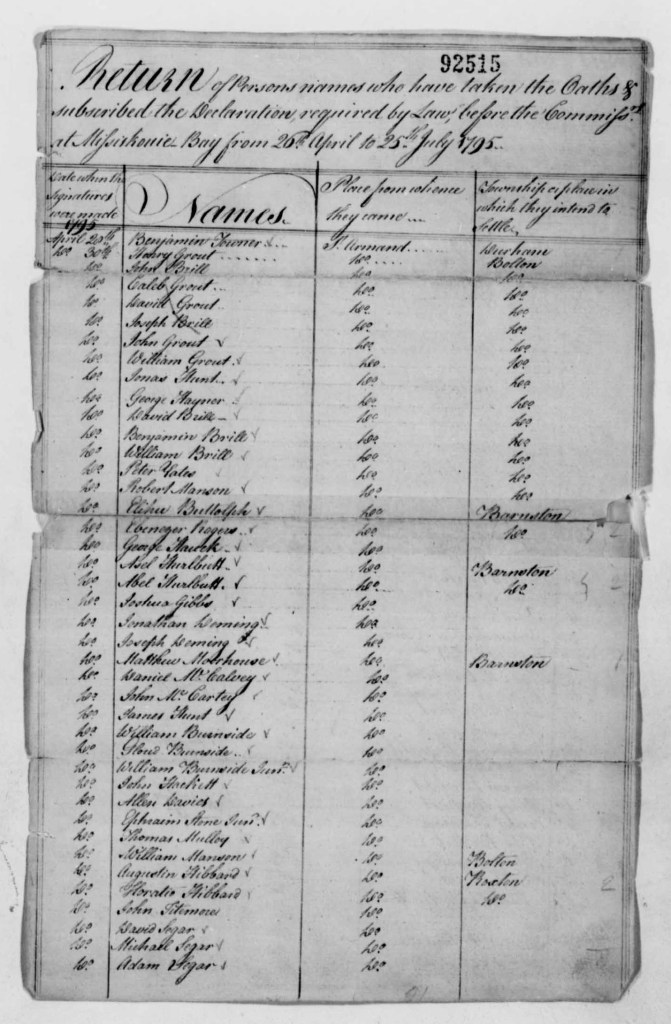

Our next post or two will focus on information found in the documents that record who “took the Oaths.” These lists were usually titled something like “Return of Persons names who have taken the Oaths & subscribed [signed] the Declaration required by Law, before the Commissioners at [place] from [date] to [date].” Just to give you an idea of what these Returns look like, here’s the first page of the “Return of Persons names who have taken the Oaths & subscribed the Declaration required by Law, before the Commissioners at Missisquoi Bay from 26th April to 25th July 1795.”

LAC. Full bibliographic details coming in our next post.

I think we will find these “Returns” particularly helpful as we sort through the various Clarks—from Canada, the UK and the USA—that sought Crown lands in Lower Canada during the 1790s and early-1800s, as each “Return” records the following very useful information:

• the date the oaths were [administered and] signed by the applicant

• the name of the person taking the oath

• the “Place from whence they came” and

• the “Township or place in which they intend to Settle.”

For petitioners desiring lands in Stanstead or other nearby townships, it appears that the appropriate location to meet with the Lower Canada land commissioners—or their representatives—and take the oaths was at Missiskouie [Missisquoi] Bay, Lower Canada. I have found a number of the mid- to late-1790s returns from the Missisquoi Bay commissioners and I’m currently reading through those documents and making lists of men with Clark(e) surnames (from all locations) as well as other Vermont or New Hampshire emigrants that “took the oaths” and may be relevant to our search for JMC’s roots.

The list making is taking some time, so I may not be back for a few days. See you soon(-ish).