Today’s post is a special one: our first guest post on Clark House Historian! It’s an excellent, beautifully illustrated introduction to the very early history of the Township of Stanstead and the often contentions relationship between the two Leaders that made it happen, Col. Eleazar Fitch and Issac Ogden, Esq. I hope you enjoy the piece as much as I did. Many thanks to guest author Jeffrey Packard and Heritage Ogden – Patrimoine d’Ogden for permission to publish this on Clark House Historian. See my postscript, below, for more on the author and his organization. For readers new to this part of Québec, the Municipality of Ogden is, generally speaking, the southwest corner of the historic Township of Stanstead, one of two reputed birthplaces of Jonathan M. Clark. And, as always, be sure to click on each image to open larger, higher-resolution versions in gallery view or a new window.

Eleazer Fitch, Isaac Ogden, and the Stanstead Township Grant: a strained attorney-client relationship

Dr. Jeffrey Packard, president, Heritage Ogden – Patrimoine d’Ogden. Copyright © 2023 by Jeffrey Packard, Heritage Ogden – Patrimoine d’Ogden.

Toponomic Namesakes

There is Fitch Bay and the Municipality of Ogden, but few realize that their respective namesakes had a five year long and not always amicable relationship as the two men both separately and collectively attempted to secure a land grant of 40,000+ acres on the east side of Lac Memphrémagog. This article describes the lead-up to the formal granting of the Patent for the Township of Stanstead in 1800, and provides the story of these two Loyalists, who were pivotal in the early history of the area.

Colonel Eleazer Fitch

Eleazer Fitch was born August 29th in 1726 in Lebanon, Connecticut to relatively affluent parents. As a young man he attended Yale where he studied law. He was described as broad and handsome and at 6’ 4” and 300 lbs he was most certainly an imposing figure for those days. At age 19 he married Amy Brown and eventually their family grew to 12 children (8 daughters and 4 sons). He fought in the Seven Years War where he served as a major of the 4th Connecticut Regiment, and was involved in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. He was a successful business man, and furthermore had business interests in association with the Governor of Connecticut. He was also heavily involved with land speculation in Pennsylvania.

At left, Windham, Connecticut circa 1826. At right Eleazer Fitch house on Zion Hill in Windham. Exterior of house modified in late Victorian times, original façade would have evident Georgian symmetry and simplicity. Built in 1763, the house burnt in 1923.

In 1763 he built a substantial mansion in the town of Windham. He was the representative of Windham County in the Connecticut General Assembly and was later elected the county’s High Sheriff. Because of his Tory sympathies he was stripped of that post in 1776, and in 1778 Fitch was brought to trial for his vocal opposition to the revolution. He was held in such high regard by his fellow townsmen, that he was acquitted of all charges. Nonetheless his family’s livelihood and physical safety were in significant jeopardy, so Fitch and his wife and their 15 year-old son George (the 11th of 12 children and youngest son) sailed from New York as UEL’s [United Empire Loyalists, -Ed.] in September of 1783 to Nova Scotia. Shortly thereafter they moved to Quebec where he was given the post of Collector of Customs at St. Jean. He died in Chambly June 23rd, 1796, in his 70th year.

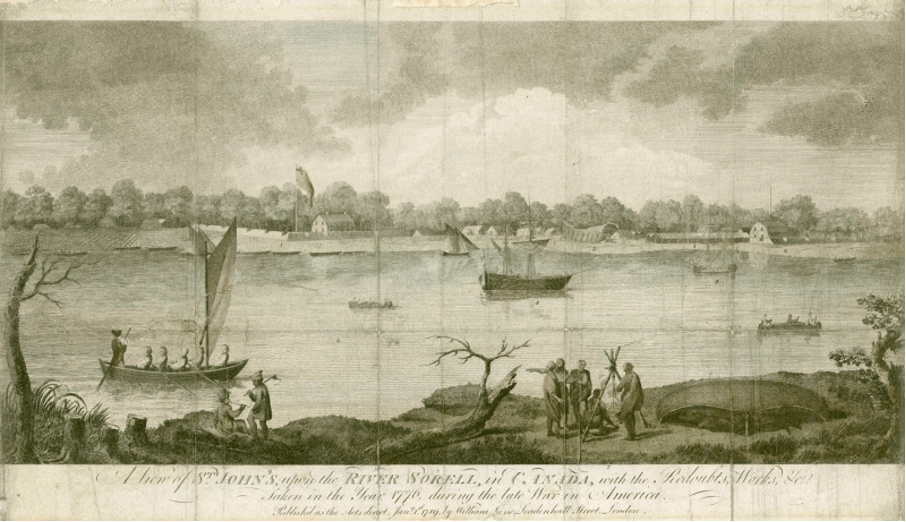

St. John’s (St. Jean) on the Sorell River (aka Richelieu River) in circa 1776. St. John’s then consisted of the fort (at left), some boat building sheds and some barracks.

Judge Isaac Gouverneur Ogden

Isaac Ogden also had an affluent upbringing. Born on January 12th 1740 near Newark, he was the eldest of six surviving children of David Ogden, a justice of the Supreme Court in the colony of New Jersey. He studied law at King’s College (now Columbia University) and was considered a distinguished jurist. The Ogden family had divided loyalties during the revolution but Isaac, along with his father and two of his brothers, after briefly flirting with the rebel cause, became staunch supporters of the Crown. Two other brothers, Samuel and Abraham, joined the rebels. In 1777 he moved his family to the British stronghold of New York and in 1783 was evacuated by the fleet to England. In 1788 he was appointed a justice of the Admiralty Court at Quebec and in 1792 or 1793 he was appointed Puisne Judge of the Montreal District (Court of King’s Bench), where his family then moved. We are told that he was a man of cheerful disposition, “sterling integrity and great moral worth”. Further, “ his manner on the bench was impressive for its energy and acuteness, and his legal opinions were delivered with perspicuity and decision”. While attending to his judicial duties he was taken with a “painful and incurable disease brought on by the sedentary nature of his profession”. His biographer states that “when not in bed he never failed to appear in his seat on the bench, but the heroic struggle had to be given up” (Wheeler, 1907). By 1818 his health had deteriorated significantly and he left for England where he underwent and survived “two painful and dangerous operations”, although we are told the procedures did not “stay the disease”. Ogden never returned to Canada and he died in Taunton, Somerset County, England on September 10th, 1824 at the age of 85

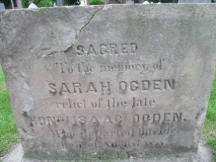

Isaac was married twice, but his first wife, Mary Browne, died in 1772 at the age of 26. Three daughters came from this marriage. In 1774 Isaac married Sarah Hanson, and she bore him 6 sons and two daughters. Two of his sons in particular made their mark in Canadian history, Charles Richard Ogden, was Attorney-General for Lower Canada and prosecuted the Patriote insurgents following the ‘37-38 rebellion. Peter Skene Ogden; was a notorious fur trader and explorer who worked in Saskatchewan and the Oregon Territory for the Northwest Company, and eventually for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Following Isaac’s death, his widow Sarah returned from England to Trois Rivières to live with her son Charles.

Left: Profile portrait of Isaac Ogden by Aegidius Fauteux (1876-1941) – but sketched long after Ogden died and it is unclear on what it was based. Possibly Fauteux used a pre-existing portrait or miniature, or perhaps it is a composite based on the likeness of his sons, for whom photographs exist. [Right: Gravestone of Sarah Ogden (1754-1838), St. James Cemetery, Trois-Rivières, Quebec, Canada. -Ed.]

Pleasant Lands

Surviving records from the Land Committee of the Province of Quebec, which in 1791 would become Lower Canada, indicate some significant interest in the lands surrounding Lake Memphremagog, starting in the early 1770s. This interest came solely from transplanted and/or non-resident Americans, and not from the Canadian populace. It may have been relatively common knowledge in the northern British colonies that the lands east of the big lake, had good agricultural potential, for a manuscript map drawn in 1756 by Samuel Langdon of New Hampshire is annotated in the region east of Memphremagog, as “A high pleasant Plain ”. That same map was printed in 1761 and widely distributed and in this version the annotation reads “A Pleasant Plain Country”. Major Robert Rogers in 1760, on his map made after the St. Francis Raid, referred to the same area as “Pleasant Lands”, although he may have just been parroting Langdon, for he carried the latter’s map on his raid and retreat.

Small portion of published map of New Hampshire by Joseph Blanchard and Samuel Langdon printed in 1761.

Following the demarcation of the boundary between Quebec and New York (get article “Good fences make good neighbours,” here) a survey that crossed Lake Memphremagog and confirmed the suitability of the terrain, a huge tract of land on the east shore of Lake Memphremagog, amounting to 92,000 acres, was petitioned for in November of 1772 by the American John Jennison, but his petition was denied.

After the American rebellion started, and even for an extended period following the conclusion of the War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1783), the region was still considered a useful buffer region, and certainly not one to be settled by republicans of dubious politics and loyalty. Even Loyalists were refused permission to settle in the region and were shuttled either towards the west (to the area that would be known as Upper Canada and eventually Ontario), the Gaspé region, Isle St Jean (PEI), Nova Scotia, or the region that was to become New Brunswick. There was even some thought given to transplanting Canadiens into the border region to serve as a bulwark against Yankee settlers and their dangerous ideas. As stated by Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor-General of the Province of Quebec “The frontiers should be settled by peoples professing a different language, and accustomed to other laws and government from those of our restless and enterprising neighbours of New England” (quoted in Abbott,2014,p.69).

The Dam Bursts

By the late 1780s, due to the influx of Loyalists, a significant minority of residents in what was then a much larger Province of Quebec, were demanding some form of representative government, the ability to own land in fee and common socage, and access to English common law. In 1791 the British parliament passed the Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act (commonly referred to as the Constitutional Act), which divided Quebec into Upper and Lower Canada. The act provided for elected assemblies for the two new provinces, and preserved in each jurisdiction those institutions favoured by the resident majorities (English and French respectively). It also was meant to provide income (hence the Act’s title) to support both the Protestant clergy and the Crown. This desire by the Home Government to transform some its vast land holdings into income, and thereby ease the colonial burden, was the driver that led to a policy shift on the frontier waste lands. This policy shift was to become a land speculator’s dream.

Most Loyalists had lost everything in the rebellion and many, particularly those who once had both influence and affluence, understandably attempted to regain their status and financial well-being once in Canada. A perceived potential short-cut was land speculation. One such individual was Colonel Eleazer Fitch. In a petition to Lord Dorchester dated June 20th 1788, Eleazer Fitch on behalf of 100 associates, asked for a land grant of some 125,440 acres, on the east side of Lake Memphremagog and just north of the Province Line. The petition was held in abeyance as the government in England had yet to decide how to dispose of its frontier “wastelands” in Quebec. However on the heels of the Constitutional Act, on February 7th of 1792 Lt. Governor Alured Clarke proclaimed the terms upon which new lands in Lower Canada were to be granted. The terms of settlement included land ownership based on free and common socage. No specific mention was made of the area of the future Eastern Townships, but it was well understood that these, and all regions outside of the established seigneuries, were to be included.

A great start quickly stagnates

By the early spring of 1792, barely a month after the publication by Lieut.-Governor Alured Clarke of the Terms of Settlement, Fitch had employed Isaac Ogden as his attorney to promote his petition in front of the Land Committee of Lower Canada. Ogden’s efforts (and influence) evidently paid off as the Land Committee soon thereafter recommended that Eleazer Fitch (as leader) and his associates receive a Township of 10 x 10 miles (100 mi2), upon fulfillment of certain obligations. Ogden and Fitch successfully launched a plea to the government to receive compensation for costs of being leaders, conditions not available in Clarke’s Terms of Settlement. A survey of the external outline of the Township was promptly completed (by August 30th 1792) by deputy-surveyor Joseph Kilborn, a fellow émigré from a Connecticut Loyalist family. Ogden, early on, wanted in on the deal, and by September of 1792 the two men had agreed to a partnership where expenses (which would be considerable, upwards of $203,000 for the surveys and Patent fees alone in today’s money) would be split 50/50. Isaac Ogden was to handle affairs in Quebec City, whilst Eleazer was to manage the associates and the surveying. However the process thereafter proceeded at a snail’s pace, and eventually ground to a complete halt.

By late 1794 the two were no further ahead in obtaining their land and evidently their partnership had soured. Communications between the two stopped (at least preserved civil ones!) and Eleazer Fitch was petitioning the Crown by himself. When Fitch senior died in the summer of 1796, his son George, then 28, asked the Associates to recognize him as the sole leader for the Stanstead Grant and to commit to signing over to him, and only to him, 1000 acres of their 1200 acre allotments (this had become standard procedure to compensate the leader for taking on all the costs of surveying, road building and mill construction).

The Associates did this and George promptly filed a petition to the Land Committee to have himself recognized as the sole Leader of the Stanstead Patent. Judge Ogden got wind of this and quickly fired off a counter-petition (July 29th 1796).

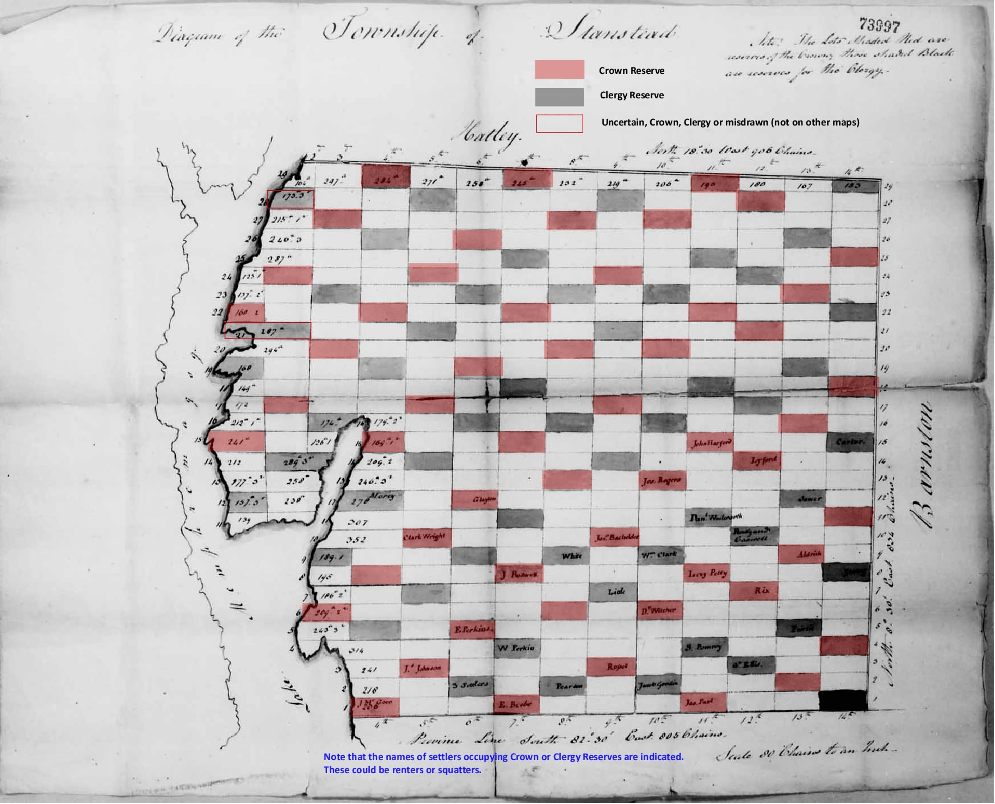

Copy of Internal survey map for Stanstead Township showing the Crown and Clergy reserves. Eventually only the southern half of this Township would be awarded to Isaac Ogden. Map dates from the period 1801-1804. [Restoration of red color on black & white archival image and additional comments on map are recent. -Ed.]

As would later be revealed, the Executive Council and in particular the Land Committee, did everything in their power NOT to award township patents to American loyalists. The confusion and competing claims by Ogden and Fitch only exacerbated an unpromising situation. Apparently recognizing that all might be lost, George and Isaac arrived at some sort of reconciliation, but when George died at Missisquoi Bay on July 12th 1798 at the age of only 30, Isaac was the last man standing. Still it took more than two full years before the Stanstead Township was granted to Ogden and his now 24 associates, and even then the patent was for only the southern half of the township (12,500 acres).

Did Eleazer or Ogden ever see the “promised land”?

Ironically it is unlikely that either Isaac or Eleazer ever saw even a square inch of Stanstead. Certainly Isaac never did, as his age and his rumoured gout, not to mention his very sedentary urban life, would have made such a wilderness trek both impractical and undesirable. By the time Ogden left Canada to seek medical treatment in England in 1818, the population of settlers on his Patent, had reached between 2,500 and 3,000. Some were there legally, but the vast majority were squatters, and attorneys for Isaac (including his eldest son David) were busy getting them to pay for deeds for the lots they occupied. They were also busy getting associates who had settled, to sign over to Ogden any land they held in excess of 200 acres.

Eleazer may have ventured into the wilderness although there is no documentation to suggest it. In a letter to Ogden on July 4th 1794 he does state “for the few years I have left to live ………… I would go and live att (sic) Magog the rest of my days.” Rather a diminished ambition for the man who had built the Georgian mansion on Zion’s Hill. For just under a decade Eleazer had attempted to get a Patent (a land grant) for Stanstead Township. Prior to realizing his dream, Eleazer died at Chambly on June 23rd, 1796, in his 70th year. His wife was left somewhat destitute and pleaded with the government for a pension in consideration of her husband’s work as a Customs officer. A payment of $200 was eventually granted to the widow. Sometime after her son George died, Amie (Amy) Fitch moved to be with relatives in Castleton, Vermont where she died on August 25th, 1799.

[Gravestone of Amy Fitch, widow of Eleazar Fitch (c. 1726-1799), Congregational Cemetery, Castleton, Rutland County, Vermont. -Ed.]

Eleazer’s son George evidently was on the ground and was intimately involved with carrying out the internal survey (i.e. breaking the Township into Lots and Ranges, each Lot being approximately 210 acres in size). In his twenties and with no formal training in surveying, it is likely he served as an assistant or helped with the logistical aspects of the survey that was being carried out by Joseph Kilborn.

References

Abbott, Louise 2014 Memphremagog: An Illustrated History Volume 1. Georgeville Press, 308pp.

Wheeler, William Ogden 1907 (reprinted 2016) The Ogden family in America Elizabethtown branch and their English ancestry; edited by Lawrence Van Alstyne and Charles Burr Ogden, 660pp.

Postscript – Clark House Historian Reed Perkins

Thanks again to Jeff Packard and the good folks at Heritage Ogden – Patrimoine d’Ogden for making today’s guest post possible. By the way, I had to re-format the original essay’s print-orientated layout just a bit, in order to fit the more linear/vertical aspect of the blog. My apologies for any infelicitous changes.

Heritage Ogden – Patrimoine d’Ogden has a very interesting and informative bilingual website: in English and en français. If you are interested in Stanstead and Eastern Townships history, be sure to visit the site. And don’t miss their bilingual Downloads–Télécharger page, which was the original source of today’s guest essay, and has a number of other, similarly well-written and illustrated essays on other aspects of Ogden/Stanstead history.

Today’s essay, by the way, was also incorporated into a published history of the Municipality of Ogden. Jeff Packard explained that this essay was one of several “written as initial stabs at compiling a short history of Ogden (detached from the Township of Stanstead in 1932). The history was successfully completed by Heritage Ogden in 2022 as part of Ogden’s 90th anniversary celebrations. It is available online (by chapters),” in French (here) and in English (here). “The book is available in hardcopy form for $25 Cdn (plus postage) from the Municipality.”

As for me, I’m still sorting and annotating an ever-growing number of Clark-related documents from the LAC database of Land Petitions of Lower Canada, 1764-1841. I’ll begin posting those in our next edition of Clark House Historian and we’ll begin our catalog of Clarks in Lower Canada, 1780s-1840s. See you then.

Pingback: Searching for JMC’s roots: Navigating the “Land Petitions of Lower Canada, 1764-1841” | Clark House Historian

Pingback: Searching for JMC’s roots: Stanstead’s original Associates’ petition, 1792 | Clark House Historian

Pingback: Searching for JMC’s roots: another (!) Stanstead Associates petition, 1792 | Clark House Historian

Pingback: Searching for JMC’s roots: Nope, not our Clark family… | Clark House Historian