A tale in four news clippings

As you know by now, we believe that Jonathan M. Clark was born or raised—or both—in or near the Township of Stanstead, Lower Canada. Who his parents were, where they came from, and what happened to them afterwards, are important questions that we have yet to answer. There are two main stumbling blocks. On the one hand, reliable birth, marriage, death and similar records for this part of Lower Canada and northern Vermont do not begin to appear on a regular basis until a decade or more after JMC’s birth in 1811/1812. And at the same time, the CLARK surname is unbelievably common in New England and the adjacent parts of English-speaking Canada. There are just too many Clark families listed in relevant indexes and archives to even begin a useful search; for a productive search, we need a way to narrow the list to only those Clarks that might be related to JMC.

So one of my first steps in this (renewed) search is to go Clark-hunting among the larger archival sources of Lower Canada, record the potentially-relevant Clark-related information and (full) names that I find, and make a big list of persons named Clark that were in or near Stanstead between about 1790-1830. If we get really lucky, we”ll find specific records of JMC, his parents, and his family. More likely, we’ll end up with a massive list of people named Clark, and from that list we can see which of these Clarks stand out as likely suspects, identify—where possible—which Clarks are definitely not “our” Clarks, and proceed from there.

For the next several weeks our name collecting expedition will be focused on the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) database of Land Petitions of Lower Canada, 1764-1841. I suspect many of our U.S. readers will see that and wonder: why waste time in that seemingly arcane archive? (Our Canadian readers will probably nod their heads and think, yes, that sounds like a very logical place to look for early Clark and Stanstead documents).

A history in 4 newspaper items

So for those readers whose knowledge of Canada history is spotty at best, let me give a very, very brief explanation of a few bits of pertinent local history, including the Loyalist issue, how Québec became Lower Canada, and how JMC’s ancestors—and their relatives and neighbors—might have been enticed to move to Lower Canada, using four contemporary newspaper clippings.

The Loyalists (1788)

If you lived in Vermont, New Hampshire, or upstate New York in the decades following the American Revolution, you might have kept abreast of current events by reading the local newspaper. One topic of concern was the fate of the Loyalists, American colonists that had remained loyal the the Crown during the war. This “Extract of a letter from a gentleman,” written in Québec and dated March 19, 1788, explains:

[Fitch, Col. and Loyalist settlers go to Lower Canada], [Bennington] Vermont Gazette, June 23, 1788.

Many Loyalists did settle in Québec, and were granted land by the Crown. Most of the Loyalists settled in what would become the western part of Lower Canada, west of Lake Memphremagog, in the lands south of Montréal and north of Lake Champlain. Other Loyalists would settle, or try to settle, in the newly-opening Eastern Townships, on the eastern side of Lake Memphremagog and north of Vermont and New Hampshire. Were any of our Clark family ancestors Loyalists? We will look into that in a few weeks. And take note of Connecticut Loyalist Col. Fitch. That would be Col. Eleazar Fitch, war veteran, land speculator, and one of the “leaders” in the founding at least two townships in Lower Canada, including Stanstead. (We will have more on Col. Fitch and his associates in the next few posts.)

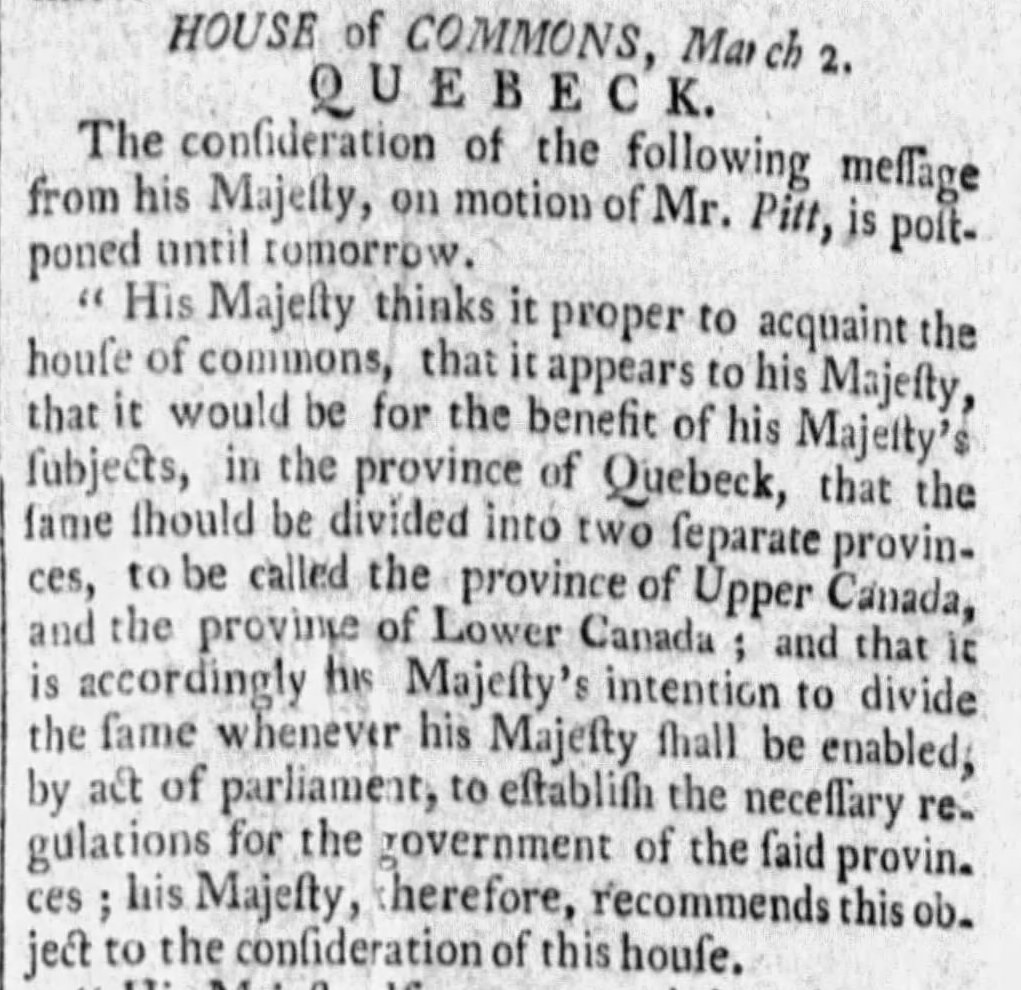

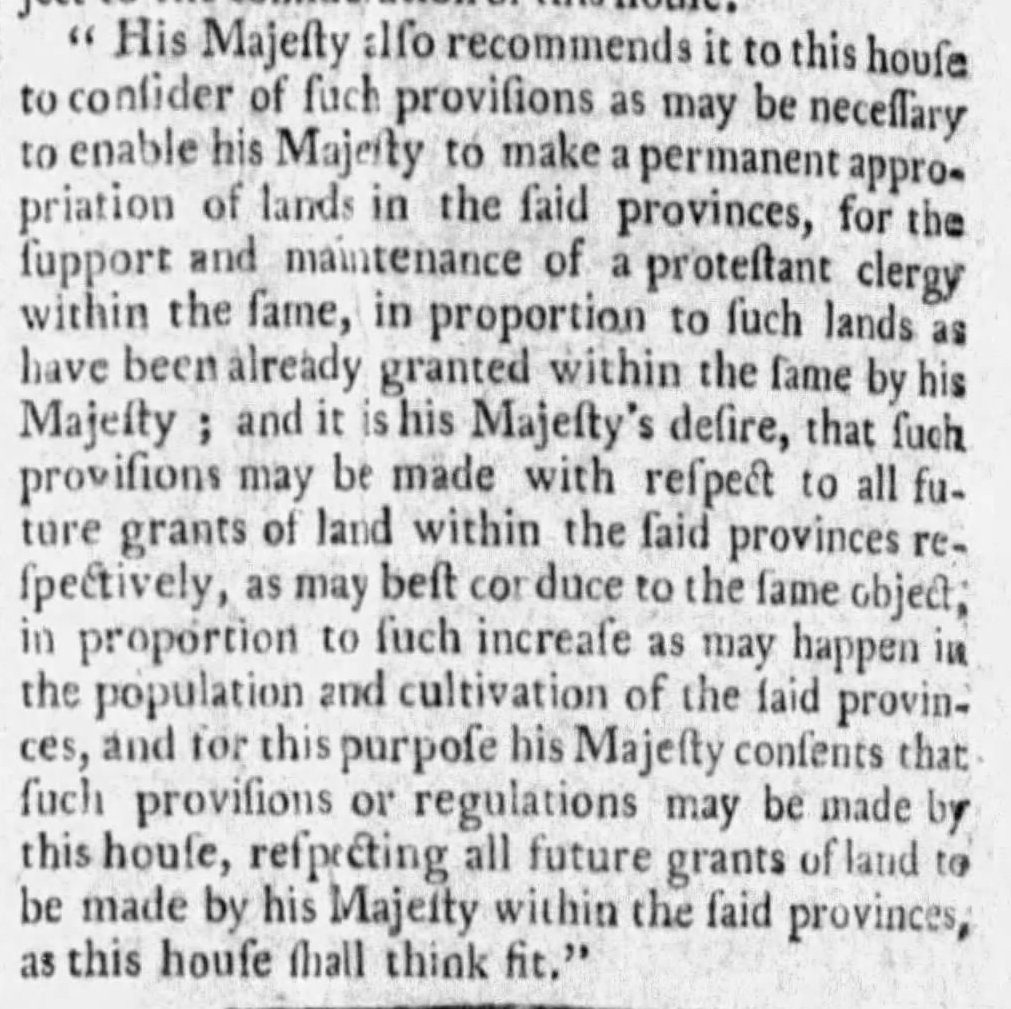

Québec (1791): It’s too big, and needs more (English) settlement

Reading the [Windsor] Vermont Journal of May 17, 1791, you would have learned that King George III (yes, that King George III) was proposing changes to the governance of his provinces in North America. In particular, he intended to divide the massive Province of Québec into two, still large, but more manageable parts.

His Majesty also wanted to make provisions for distributing the unsettled parts of this land to his subjects, while reserving an as-yet unspecified portion of such lands for the eventual use or financial benefit of the Protestant clergy and the Crown. By the way, as we move forward in our search we will note the many land-ownership conflicts that arose regarding these “Crown and Clergy” lots during the settlement of Stanstead and the other Eastern Townships.

“Quebeck.” [His Majesty has plans for development], [Windsor] Vermont Journal May 17, 1791.

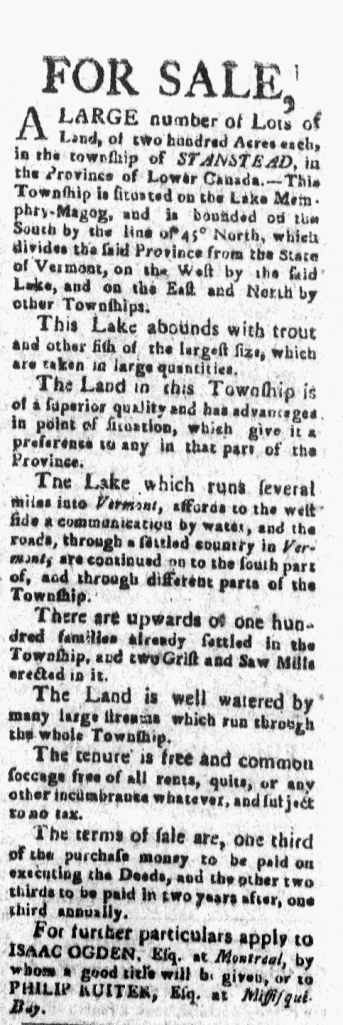

Stanstead (1800) – “Location, location, location”

You know the old real estate joke: What are the three most important things to consider when buying a home? “Location, location, location.” That appears to have been true in 1800s Lower Canada, too. By 1800 Col. Eleazar Fitch had died and his attorney and co-leader, Montréal land broker Issac Ogden, had taken his place. (Much to the dismay of Col. Fitch’s heirs. More on that next time.) In late 1800 and early 1801, Ogden enthusiastically promoted Stanstead settlement with this advertisement, placed in several Vermont newspapers:

“For Sale.” [Land in Stanstead] Spooner’s [Windsor] Vermont Journal, December 23, 1800, p 3

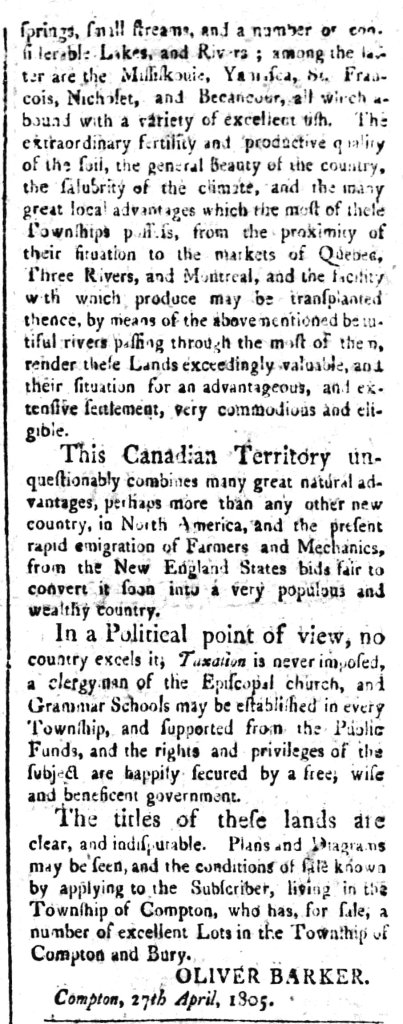

But wait, that’s not all! (1805)

By the time this next article was published in 1805, a very large number of the Stanstead lots had been sold to investors (including well-placed government officials). A smaller percentage of lots were actually owned and occupied by immigrants from the U.S.A., the English-speaking community of Lower Canada and immigrants from the U.K. The land was still sparsely populated, and quite a few of the original settlers were occupying and improving land for which they did not have clear title. Many settlers were, in essence, squatters on lands owned by wealthy investors, or officially reserved for the Crown and Clergy.

With Stanstead lots mostly spoken for by 1805, land brokers like Compton’s Oliver Barker, the author of this advertisement, were promoting settlement in more recently opened, or less-settled, townships, such as Barford, Bolton, Potton, Melbourne, Shipton and Stoke, as well as additional township lands farther north, west and east of Stanstead.

“Lands for Sale in the Province of Lower Canada,” [Peacham, Vermont] Green Mountain Patriot, June 4, 1805, p 3.

With the large number of associates and actual settlers in these townships, many named Clark, we will not be able to investigate every possible “Clark” clue in all of the Eastern Townships. However, there are some Clark settlers that I have heard about from other sources—for example, a David Clark and family that were early settlers in Melbourne Township—that we need to examine and see what, if any, connection they may have to Jonathan M. Clark’s family.

Coming up…

I’m sorting and annotating a large number of Clark-related documents from the LAC database of Land Petitions of Lower Canada, 1764-1841, and I’ll begin posting those shortly. But before that, our next post will be a special one: our first Guest Post on Clark House Historian! It’s an excellent, beautifully illustrated introduction to the very early history of the Township of Stanstead land grants and the often contentions relationship between the two Leaders that made it happen, Col. Eleazar Fitch and Issac Ogden, Esq. That post should be up in a few days. See you then!

Oh, so interesting …. Nina

LikeLike