This is an expanded—and lavishly illustrated—version of a piece that first appeared in the Summer | August 2023 edition of the Jonathan Clark House Newsletter. I hope you enjoy the extra information, images, and the vintage writing tips.

UPDATED: August 27, 2023, to clarify provenance of Robert Beveridge’s writing desk.

One of the ways we collect, preserve and share the history of the Jonathan Clark House and the early settlers of Mequon and Thiensville is by acquiring and interpreting furniture, tools, clothing, and various accessories that would have been familiar to the Clarks and their neighbors. One particularly fine item in our collection is this box, a treasured heirloom generously donated to the Clark House collection by JCH Friend Frederick Bock.

Photo courtesy of Tom Gifford (2023)

When closed it measures about 16 x 6 x 10 inches. It is made of wood, stained a rich golden brown. On the top is a brass plaque inscribed Rt.[Robert] Beveridge / 1854. And there’s a lock on the front. Why is that?

Writing desk, 1854

Because this is more than a nice box, it’s a mid-1800s portable office, containing all that one needed to conduct professional or personal business before and during the Clarks’ era. Fold open the lid and it becomes a writing desk, also known as a lap desk. The British call this a writing slope; the French sometimes refer to it (and much larger furniture for writing) as an escritoire.

Photo courtesy of Tom Gifford (2023)

It features an ergonomic slanted writing surface and, at the high end of the desk, spaces for quills or steel pens, ink bottles, penknives and sealing wax. And each half of the cloth-covered writing surface hinges open to provide space for storing fresh paper, letters received, and more.

Photo courtesy of Tom Gifford (2023)

The well-equipped desk

Whether writing for business, school, correspondence or pleasure, your writing desk would need paper, ink, pens and other supplies. And in pioneer days, if you lived in the rural parts of the country, you could often get what you needed from a local peddler.

Bush, Charles Green, artist. The peddler’s wagon / drawn by C.G. Bush, 1868. Library of Congress.

And if the peddler didn’t have what you needed, the stores in cities like Milwaukee did. In 1844-1845, Milwaukee’s E. Hopkins Bookstore was stocked with all the necessities:

This ad, originally published November 21, 1844, was reprinted in subsequent editions of the Milwaukee newspaper(s); this copy is from the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, January 8, 1845, page 3. Some ads were more specialized.

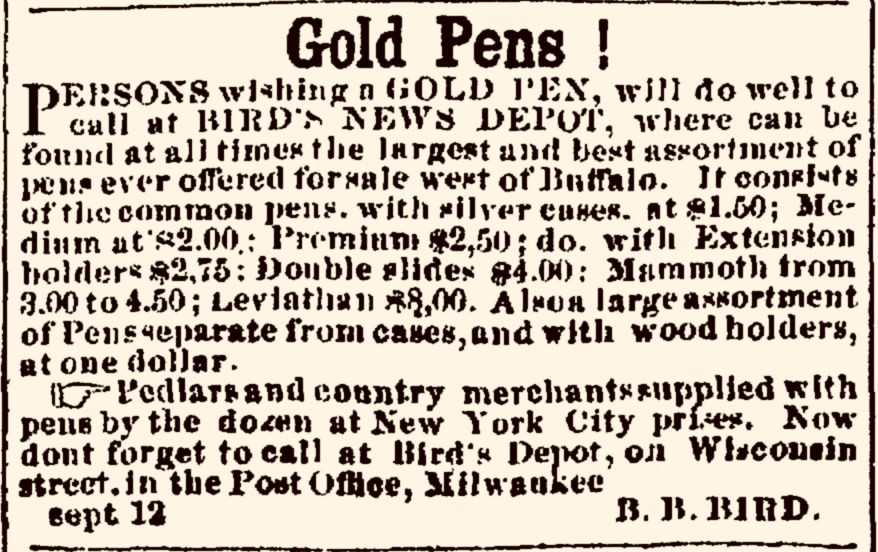

This one, from the [Milwaukee] Daily Free Democrat, November 2, 1850, page 4, touts an admirable selection of pens of all types and prices available from Bird’s News Depot, located in the Post Office on Wisconsin Street:

And keep in mind that in the 1800s, “pens” refers to the interchangeable pointy metal tip of the writing device. The “pen holder”—the part you actually held in your hand—was usually a simpler item, often made of wood. In 1850 Mr. Bird offered wood pen holders, without silver cases (but perhaps with at least one steel tip included), for $1.00. For several similar, even more comprehensive and informative, ads from the next decade, see our recent post School supplies…and more, 1850.

Good form is important

Instruction books of the era stressed the importance of proper hand position and upright posture when writing, as in this example from 1859:

Northend, Charles. The teacher’s assistant, or Hints and methods in school discipline and instruction. Boston, Crosby, Nichols, and company; Chicago, G. Sherwood, 1859, excerpt from pages 172-173. Library of Congress.

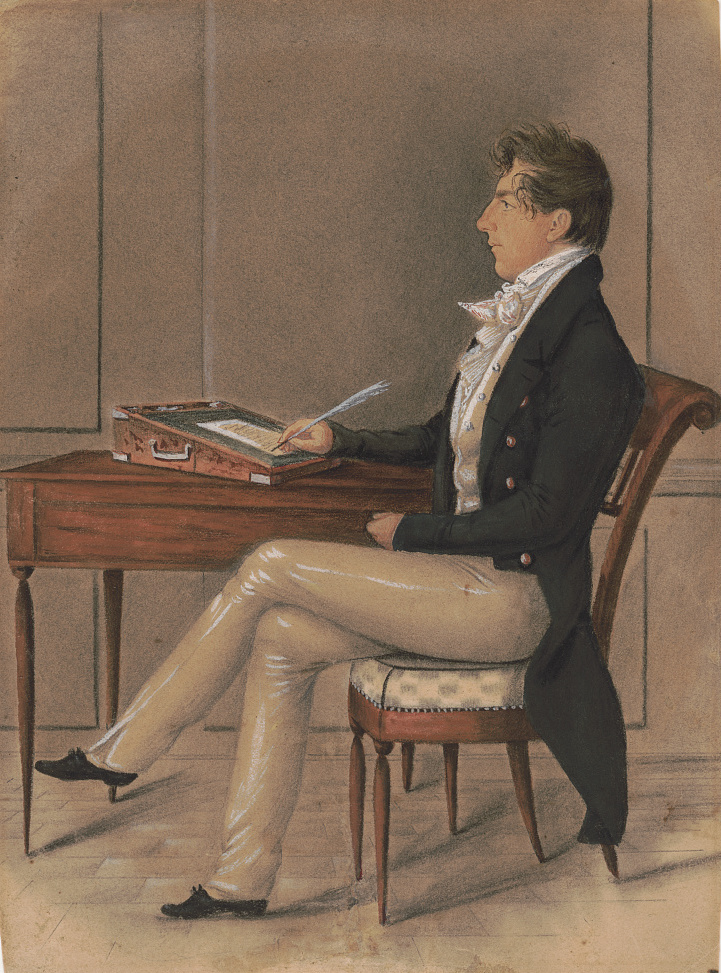

It appears that this Philadelphia gentleman—writing with the inexpensive but still popular and effective goose quill pen—learned his lessons well:

Earle, James S., artist. Philadelphia silversmith William Faber, drawing: watercolor, lead white, and graphite on wove paper, circa 1847. Library of Congress.

Who used a writing desk?

A portable writing desk, such as the one in our Clark House collection, was not a necessity on the Wisconsin frontier. But for anyone that had need of writing supplies—which could be expensive or hard to obtain at times—a desk like this was a very useful tool. With its smooth writing surface and lockable storage, a desk such as ours would have been useful to the Clark family and many of their friends and neighbors, including…

Industrious school children

Unknown artist, [Industry] , n.d., n.p., Library of Congress.

Business and professional men and women

Edridge, Henry, Portrait of a Man, Seated in Front of a Writing Desk, c. 1795-1800. Watercolor over graphite with touches of gouache (bodycolor). Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1965. Public domain.

The personal correspondent

Unknown artist. A young woman sitting at a desk, writing on a slope […], illustration for an unknown publication, n.d., British Museum, (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) non-commercial license.

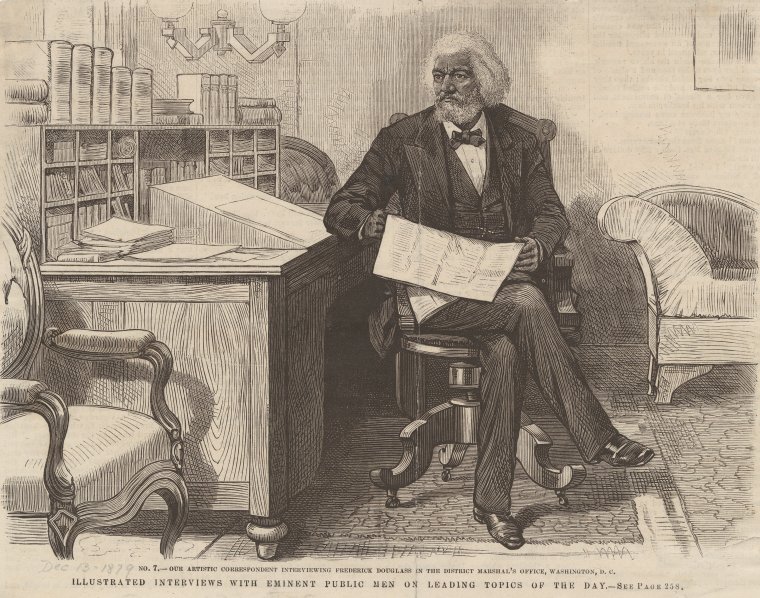

Civic and political figures

Unknown artist. “Harper’s Weekly portrait of Frederick Douglass seated at desk holding newspaper.” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1879-12-13.

And, of course, Robert Beveridge

Robert Beveridge, the original 1854 owner of our little desk, used it for many years. You can tell just by looking at the ink stains in the inkwell areas. It was then passed down through his family as a treasured heirloom until it was donated to the Jonathan Clark House. But who was Robert Beveridge?

Robert was born in Fife county, Scotland, March 20, 1825, the son of John and Cecelia (Ower) Beveridge. He appears on the 1841 census of Scotland, age 15, working as a reed maker, living in Abbotshall, Fife, with his mother and two younger siblings, William and Cecelia Beveridge. Robert’s father appears to have died or otherwise left the family, possibly before 1838; mother Cecelia was now married (?) to one David Neilson [aka Nealson]. There are two Neilson children, ages 3 and 1, apparently the offspring of their union, living with the family.

By the time of the 1851 census, Cecelia and David Nealson are living in Sinktown, Fife, with “Step Daughter-in-law” Cecelia Beveridge and three Nealson children. Robert is no longer in the household. I have not found Robert Beveridge on the 1851 Scotland census.

Robert next appears on the passenger manifest of the Ship “Driver,” arriving at the Port of New York from Liverpool, on March 14th, 1855. The manifest records Robert Beveridge, a 30 year old mechanic from England [sic], that intends to reside in Wisconsin. Comparing the 1855 date of Robert’s departure from the UK, and the inscribed date “1854” on the lid of our writing desk, suggests that the desk was made in Scotland or England and, perhaps, was a going away gift for the 19- or 20-year-old, America-bound, Robert.

I have not been able to trace Robert in the U.S. from 1855 to 1865; there is one Robert Beveridge, who filed his first naturalization papers in Foxborough, Bristol Co., Massachusetts in 1856. He might be our man, but I’m not entirely sure he is. Our Robert Beveridge next appears in Minnesota on the 1865 state census for Leon, Goodhue county, in the household of one William Williams. In 1870 Robert was enumerated in the Town of Florence (post office Red Wing), Goodhue county, at the farm of Arthur M. Wilder. Robert was now a merchant, selling dry goods, and had amassed substantial assets, namely $4,000 worth of real estate, and $8,000 in personal property.

Newspapers in Goodhue county contain quite a few reports of Robert’s activities during the 1870s. He seems to have had—and recovered from—one or two financial reverses during the decade. After a foreclosure sale of his farm in late 1870, Robert traveled to Scotland, intending to return to Minnesota the next year. He ended up staying in Fife until late-September, 1872, when he returned to Goodhue county with his new wife, Dorothea:

BEVERIDGE, Robert marriage announcement,, Goodhue County Republican March 7, 1872, p 4

Robert Beveridge – final decade

Robert Beveridge and Dorothea Hay (or May) Turner were married in Abbotshall, Kirkaldy, Fife, Scotland on February 8, 1872. For reasons unknown they appear to have separated after only a short time together, and Dorothea returned home to Kirkaldy while Robert remained in Minnesota. The Beveridge’s only child, daughter Dorothea Hay Beveridge, was born in Kirkcaldy on December 30, 1872.

Robert Beveridge remained in Red Wing, Minnesota. He was enumerated there on the 1875 state census and the 1880 federal census.He was naturalized as an American citizen at the District Court, Goodhue county, on December 16, 1879. During the last decade of his life he maintained his “Featherstone Prairie Farm” in Featherstone Township (section 29, T112-N, R15W), Goodhue county, and he pursued a career as a fire insurance agent for the Western Department of the Commercial Union Assurance Co. of London.

BEVERIDGE, Robert death notice, Sioux City (IA) Journal February 15, 1883, page 1.

Robert died February 11, 1883 and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Red Wing. He was 57 years old. He and Dorothea must have separated on amicable terms. Robert’s will, written in 1880 and probated in Goodhue county in 1883, provided very substantial legacies for his wife and daughter, as well handsome—but more modest—amounts for his step-brother, sisters and step-sisters, including sister Margaret (Beveridge) Scott, and her son, W. E. Scott.

Robert’s wife, Dorothea (Turner) Beveridge, lived until 1915 or 1916. She, her daughter Dorothea (d. 1940), and even their long-separated husband and father Robert Beveridge, are all commemorated on a family gravestone/memorial in Abbotshall Churchyard, Fife.

Post scriptum…

In short, just about everyone in the early- to mid-19th century might want a writing desk, and many owned and used one. I believe Robert Beveridge’s 1854 writing desk may have remained in the family for at least a while, and may have descended through nephew W. E. Scott’s side of the family. At an unknown time, the box, containing some Beveridge family papers, came into the possession the late wife of donor Frederick Bock, and more recently from Mr. Bock to the Jonathan Clark House Museum collection (see Note, below).

To learn more about our writing desk’s history, come see it at the Clark House. Give us a call at 262-618-2051 or send us an e-mail at jchmuseum@gmail.com to arrange a tour.

If all goes as planned, I’ll be back next time with a Jonathan Clark related “Monday: Map Day!” post centered on the earliest settlers in Stanstead, Lower Canada, around 1805. See you then!

______________________________

CREDITS:

- Special thanks to Clark House friend and photographer Tom Gifford for the excellent photographs of the Clark House writing desk.

NOTE:

- Based on new information received from Clark House director Nina J. Look (Aug. 28, 2023), I have updated the details of the provenance of the Beveridge writing desk in the Post Scriptum paragraph. It is now my understanding that donor Frederick Bock is not a descendant of the desk’s original owner, Robert Beveridge. My apologies for the error.

“ Industry, Industry, Industry!”- the teaching tips are hilarious – nothing changes. And, I want a “leviathan” pen!

LikeLike

Thanks for all the research on Robert.

Nina

LikeLike

You’re welcome!

And I’ve made an update to the “Post Scriptum” paragraph, clarifying the box’s provenance. Thanks for the info.

LikeLike

Pingback: Labor Day – a photo essay | Clark House Historian

Pingback: The search for JMC’s roots continues… | Clark House Historian

Pingback: CHH blog roundup, 2023 | Clark House Historian