Isham Day was one of the very first white pioneers to settle in the future Town of Mequon, Wisconsin Territory. I first wrote about Isham Day, and his historic house—later Mequon’s first post office, and also known as the Yankee Settlers’ Cottage—in an earlier post, River Walk. You might want to read that before continuing with today’s essay.

Isham Day was not only one of the first settlers in this area, he was active member of the small but growing community in what would become Washington and, later, Ozaukee counties. There is a lot to say about his role in the early decades of pioneer life in the Clarks’ neighborhood, some of which is already known through early local histories and various federal and local primary sources. (And he appears in six different posts here at Clark House Historian.)

One thing that is less well known is what happened to Isham Day after those early days in Milwaukee and Mequon. I wanted to know and, after an extended search, I found out. In many ways, it’s a story of the stereotypical moving-ever-westward American pioneer experience. But it’s also a story of a man trying to live a peaceful life in the midst of violence and rebellion. In our recent post, Memorial Day, 2023, we remembered some of our local men that fought and died to preserve the Union and end the scourge of slavery in “the land of the free.” Today we examine one of the many civilian casualties of that conflict: Isham Day.

Isham Day house (“Yankee Settler’s Cottage”), built 1839, Mequon, Wisconsin. The oldest house in Ozaukee county still on its original foundation. Photo credit: Anna Perkins, 2021.

Please note: sensitive or younger readers may find some of the language and events documented below to be disturbing.

Isham Day, 1809 – 1862

While Isham Day played a noteworthy role in early Mequon affairs, he was born and spent much of his life elsewhere. A quick look at the federal decennial and Wisconsin territorial censuses, and a few other sources1, will give a rough outline of his life and wanderings prior to his untimely demise:

- Born December 26, 1809, Jefferson Co., Tennessee1

- 1820 federal census, probably with his father Levi Day’s family in Ogle, St Clair Co., Illinois; Page: 122; NARA Roll: M33_12; Image: 120

- 1830 federal census, probably his father Levi Day’s family in [township not stated], Macoupin Co., Illinois; Series: M19; Roll: 23; Page: 213

- 1833, November: Isham Day married Amelia/Emily Bigelow in St. Clair Co., Illinois.

- 1836 Wisconsin territorial census, Milwaukee Co. (including the future Washington Co.), page 3

- 1840 federal census, Washington Co., Wisconsin Territory; Roll: 580; Page: 123; Image: 259; this census indicates he was born circa 1790-1800

- 1842 Wisconsin territorial census, Washington Co., page 67

- 1844 received two federal patents for land in Wisconsin territory: lot no. 2 (containing 33 and 30/100 acres) of Sec. 13, T9N-R21E (the future Town of Mequon), old Washington county, and 80 acres in Sec. 33, T4N-R16E, Walworth county.

- 1845, February: daughter Mary born in Walworth county

- 1846: Isham Day & family not found on the Wisconsin territorial census

- about 1849, migrated to Missouri, per wife Amelia (Bigelow) Day’s 1899 obituary

- 1850 federal census, Finley, Greene Co., Missouri; Roll: M432_400; Page: 313A; Image: 142

- 1860 federal census, [Post Office hard to read, looks like “Ozark”], Benton Twp., Christian Co., Missouri; Roll: M653_613; Page: 487; Image: 491.

Violence in the West

By 1860, the issue of chattel slavery in the United States, and whether and how it might continue to spread into new states and territories as the U.S. expanded westward, roiled the nation’s politics and inflamed regional passions. Tempers were particularly hot in the new states and territories that bordered the slave-owning states of the South. Violence and general lawlessness increased throughout the area following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

The years of 1854-1861 were a turbulent time in the Kansas Territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 established the territorial boundaries of Kansas and Nebraska and opened the land to legal settlement. It allowed the residents of these territories to decide by popular vote whether their state would be free or slave. This concept of self-determination was called popular sovereignty. In Kansas, people on all sides of this controversial issue flooded the territory, trying to influence the vote in their favor.

Rival territorial governments, election fraud, and squabbles over land claims all contributed to the violence of this era.

Three distinct political groups occupied Kansas: pro-slavery, Free-Staters and abolitionists. Violence broke out immediately between these opposing factions and continued until 1861 when Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29. This era became forever known as Bleeding Kansas.

During Bleeding Kansas, murder, mayhem, destruction and psychological warfare became a code of conduct in Eastern Kansas and Western Missouri. A well-known example of this violence was the massacre in May 1856 at Pottawatomie Creek where John Brown and his sons killed five pro-slavery advocates.

“Bleeding Kansas,” National Park Service

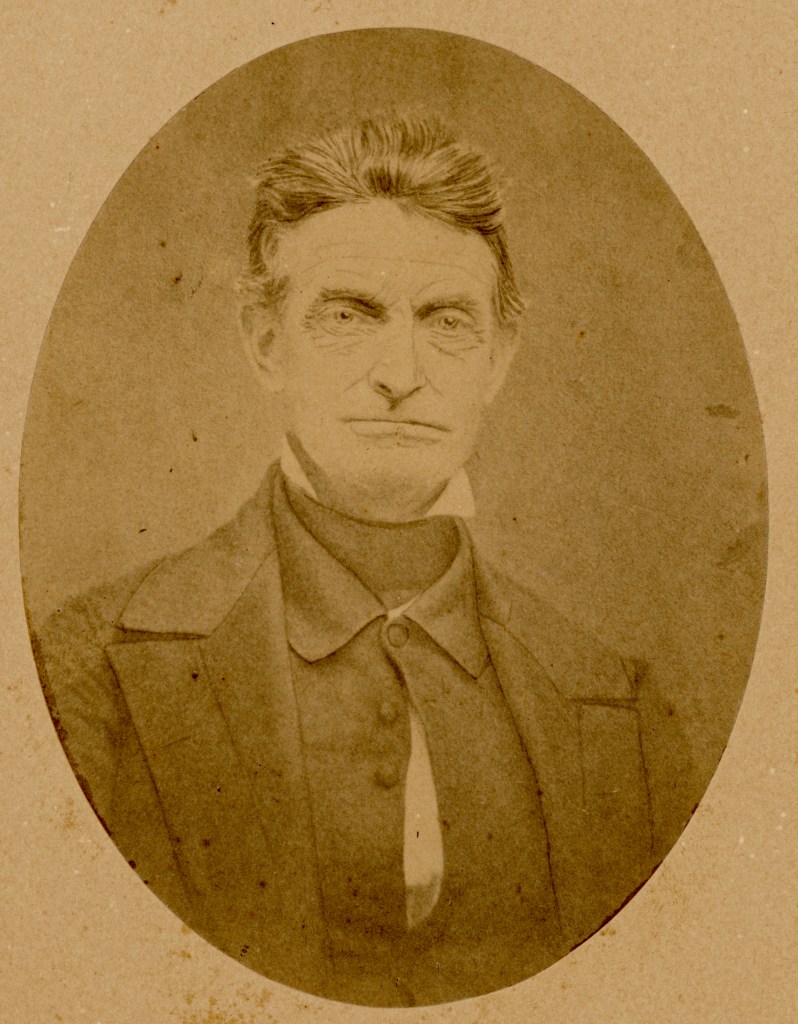

John Brown, c. 1855, the year before he led the brutal Pottawatomie Creek massacre near Lane, Kansas.2

Isham Day and his family left Wisconsin and moved to southwestern Missouri in 1849. Their first Missouri home was in Greene county; by 1860 they were living south of Greene county, in Christian county. During the Civil War, Missouri was one of the four slave-holding “Border States” that did not secede from the Union. When the war began in April, 1861, the Day family—as Union supporters living in slave-holding Missouri—must have been keenly aware of the dangers surrounding them, particularly from pro-Confederate bushwackers.

Alf Bolin, bushwacker

The “bushwhackers” were Missourians who fled to the rugged backcountry and forests to live in hiding and resist the Union occupation of the border counties. They fought Union patrols, typically by ambush, in countless small skirmishes, and hit-and-run engagements. These guerrilla fighters harassed, robbed, and sometimes murdered loyal Unionist farmers on both sides of the state line. They interrupted the federal mail and telegraph communications, and (most troublesome to the Union command trying to quell the escalating violence in the border region) the bushwhackers held the popular support of many local farming families.

Kansas City, Missouri, Public Library3

One notorious bushwacker was a young man known as Alf Bolin (or Bolen).4 An 1883 history of Greene County describes him this way:

Bolen was a terror to the Union citizens of the southern part of Greene county, as well as those of all Christian, Stone and Taney. He had killed many a man, and the Confederates detested him almost as severely as the Unionists. Among his victims was an old man, 70 years of age, named Budd, whose ears he cut off before he finished him with a revolver. This murder was committed in the fall of 1861.5

The story is repeated and enlarged upon in the subsequent Past and Present of Greene County, Missouri, 1915, which describes Alf Bolin in similar terms:

[…] a desperate guerrilla and bushwhacker and was a terror to the Union citizens living in the southern part of Greene county, as well as those of Christian, Taney and Stone. He had killed many men, one of his most atrocious murders being committed in the fall of 1861 when he cut off the ears of a man named Budd, seventy years of age, and tortured him in Indian fashion before finally killing him with a revolver. He was hated by both the Confederates and Federals.6

This 1915 description of Alf Bolin continues with this additional tale of his attacks on civilians:

The other most atrocious crime was taking Isham Day, a prisoner, tying a rope around his neck and tying rocks to the rope and throwing him into White river and drowning him.6

Isham Day’s murder

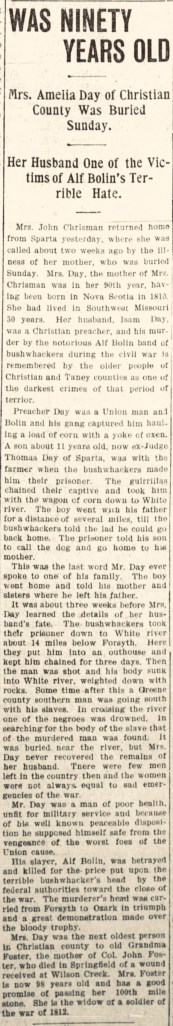

Isham Day was married to Amelia (or Emily) Bigelow in Illinois in 1833. She was yet another member of the extended Nova Scotia Bigelow family that figured prominently in Mequon’s early days.7 When Amelia Day died in in the last days of the nineteenth century, she was celebrated as the second-oldest resident of Christian county, and received a long and detailed obituary in the Springfield Leader and Press, Springfield, Missouri, on Tuesday, December 26, 1899. Ironically, only a few of that obituary’s words and details were about the deceased. Instead, most of the obituary describes—at length—the notorious murder of Amelia’s late husband, Isham Day, some 37 years before:

When the federal census was enumerated in Christian County in July, 1860, Isham Day was recorded as 51 years old and his wife, Emily, 50. They still had the two youngest of their nine children living with them: Mary, age 15, and Thomas, age 10. If the information in Amelia Day’s obituary—regarding son Thomas’s age at the time his father was killed—is correct, then Isham Day was murdered sometime between mid-1861 and mid- (or late-?) 1862. Other sources support this date range. In particular, a new (to me) Day family genealogy (see note 1, below), states that Isham Day was killed on April 8, 1862. He was 52 years old.

Now we know

Those of us that study Mequon and early Milwaukee and Washington/Ozaukee county history have heard about Isham Day. Or at least we know a few key facts about when he arrived in Wisconsin Territory and when he built his so-called “Yankee Settlers Cottage.” But until now, I didn’t know “what happened to Isham Day?”

Now we know.

Isham Day, husband, father, farmer, Christian preacher, Union man—and one of Mequon’s original pioneers—had a peaceable nature and was in poor health when, in April, 1862, he was murdered by pro-Confederate domestic terrorists. His final resting place remains unknown, an unmarked grave somewhere along the banks of Missouri’s White River.

His wife of 28 years, Amelia/Emily Bigelow Day survived him and lived another 37 years. She was buried in a small family cemetery near Oldfield, Christian County, Missouri.

_____________________________

NOTES:

- As I was finishing this article I came across an excellent source for genealogical information about Isham Day, his ancestors and descendants. It is a slim, typescript book of 52 single-sided pages called Descendants of Christopher Day of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, complied by J. Edward Day in 1959. It is available for reading online or as a free download at the Internet Archive.

The author appears to have taken pains to be accurate and well-organized and, fortunately, the info in this 1959 book agrees with, or improves upon, what I had already discovered in the other documents cited above. (Phew.) - Photo credit: Unknown photographer, John Brown, circa 1857 salted-paper photograph copy of a circa 1855 daguerreotype original, Smithsonian Institution, National Portrait Gallery. Creative Commons License CC0.

- The full essays on “Bushwackers” and John Brown’s “Pottawatomie Creek Massacre” are part of a substantial web project at the Kansas City (Missouri) Public Library called Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict,1855-1865. It has a great collection of essays, maps, images plus timeline and lesson plans devoted to the subject. Highly recommended. The essay on “Bushwackers,” excerpts quoted above, was written by Tony O’ Bryan, University of Missouri—Kansas City.

- As is the case for many of the Missouri Civil War era bushwackers, there are many stories, myths and rumors surrounding the life of Alf Bolin/Bolen, but the facts are harder to come by. In sorting through the misinfomation, I found these links to be particularly useful:

• Alf Bolin’s necessarily incomplete FindAGrave is here. It provided birth and death dates and places; the facts here are unsourced, but were useful for leading me to:

• Wood, Larry. “Missouri and Ozarks History” blog (accessed 31 May 2023): Alf Bolin, Just the Facts, part 1 (this is particularly useful and has information on several primary sources)

• Wood, Larry “Missouri and Ozarks History” blog (accessed 31 May 2023): Alf Bolin, Just the Facts, part 2

• Hobbs, Patti, “Christian County, Missouri, Genealogy” blog, “Alf Bolin the Ozarks Bushwacker, part 1”, with links to parts 2 and 3. - History of Greene County, Missouri […] Illustrated. Western Historical Company, St. Louis, 1883, page 459. Available as a free GoogleBook.

- The transcribed material is taken from Fairbanks, Jonathan Edward and Clyde Edwin Tuck, Past and Present of Greene County, Missouri, Early and Recent History and Genealogical Records of Many of the Representative Citizens, in 2 vols., 1915. The Alf Bolen information is found in vol. 1, chapter 11 – Military History, Part 9 – Greene County Military Organizations. The book is available in an online transcription, courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library (Missouri); they give a publication date of “c. 1914.” The link to the beginning of chapter 11 is here, The table of contents for the complete vol. 1 is here. The library has digitized seven Greene County histories; links to all are here.

In describing Alf Bolin, it’s worth noticing that both the 1883 and 1915 Greene County histories take pains to mention that “the Confederates detested him almost as severely as the Unionists” [1883] and “He was hated by both the Confederates and Federals” [1915]. This appears to be special pleading from these post-war authors, who suggest—here and elsewhere, in both books—that they favor “Lost Cause”-type explanations and biases regarding the war, its causes, the regular and irregular Southern combatants, and the lamentable suffering of the county’s (pro-Southern) residents during and after the war. On the other hand, it’s clear —as late as Amelia Day’s 1899 obituary—that the pro-Union Isham Day family did not support these revisionist beliefs, at least in regard to the deeds of Alf Bolin and his gang of Confederate sympathizers. - I have still not had the time to untangle the various lines of the Bigelow family genealogy. At some point, someone should really look at the history and genealogy of Mequon’s Bigelow, Strickland, Loomer, Loomis and Woodworth families. They—and others—all came from Nova Scotia to Wisconsin Territory in the 1830s and ’40s. They were friends and neighbors of Jonathan and Mary Clark. And we really only know the outlines of their lives, at best. These were large, inter-related families and important parts of early Washington/Ozaukee county history. I’m afraid I won’t have the time to give their stories a proper look.

As I was wrapping up the edits and credits for this post, I ran into this site: http://bigelowsociety.com/rod/dan692c3.htm This is the “Daniel Bigelow” page from the Bigelow Society website. Daniel was the father of Emily/Amelia Bigelow, the wife of Isham Day. This site looks promising for sorting out some or all of the Bigelow members of the Nova Scotia immigrants to Mequon.

Awesome research!

LikeLike

Pingback: Thomas Day: farmer, prospector, preacher | Clark House Historian

Thanks for your (usual) meticulous research. Please come visit the museum soon ! Sam

LikeLike

Thanks, Sam. I’m glad you enjoyed the post.

And, yes, the postal museum at the Isham Day House is on my “to do” list this summer.

Cheers,

Reed

LikeLike

Pingback: Memorial Day, 2024 | Clark House Historian